| From Quern to Computer; a history of flour milling by Martin and Sue Watts covers a wide range of topics and this series of emails will summarise each one separately. It is clear that by the time of the Norman Conquest mills were regarded as important manorial assets. No manor was properly equipped unless it had a mill. This is demonstrated by the 6,000 plus recorded in Domesday Book, the result of the survey undertaken in 1086. Considering the number of mills recorded it is perhaps surprising that the remains of so few medieval watermills have been found through excavation. However, excavations on the sites of St Giles Mill and Minster Mill in Reading (below), for example, demonstrated that subsequent rebuilding had removed much of the evidence for earlier mills. |

(MCFC-90002)

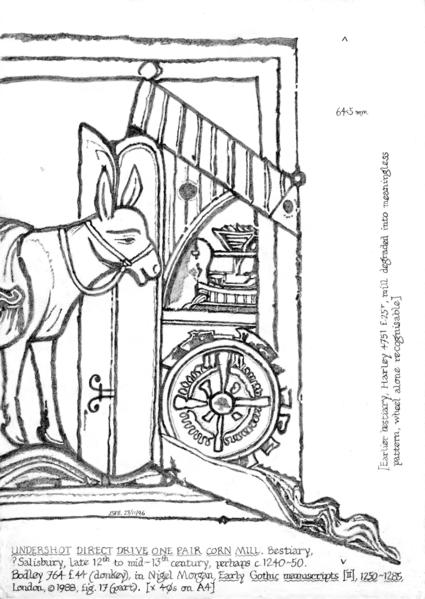

| Watermill sites are often both multi-period and multi-phase, which can make their interpretation complex. Such evidence as has been found, including illustrations, shows that later medieval watermills were generally small buildings containing a single pair of millstones driven by a vertical waterwheel. In order to increase capacity, and provided there was an adequate water supply, a second and sometimes a third mill might be added and the description ‘two mills under one roof’ is sometimes found in documentary sources. Fountains Abbey mill, North Yorkshire is an important and impressive early example of the latter. |

The earliest written references which specifically mention windmills date from the 1180s. In a well-documented case of 1191 Abbot Samson of Bury St Edmunds ordered the destruction of a windmill which had been built on glebe land without his permission by Herbert the dean. By the early 14th century windmills had also appeared in the north-west, at Upton-in-Widnes, Lancashire and Haulton, Cheshire, for example. While it has been suggested that windmills were built by manorial lords to supplement rather than supplant watermills, in some areas where the water supply was intermittent or the topography less favourable to providing a good fall of water, windmills became a common sight in the late medieval landscape.

Carving of a post mill on an early 16th-century church bench end at Bishop’s Lydeard, Somerset showing part of the trestle buried in the mound. Next to the mill are the miller with a measure for taking his toll and his packhorse

(MWAT-016)

Stone tower mills were built from at least the end of the 13th century, for example within the outer bailey of Dover castle, but stone-built mills generally appear to have been status symbols. The dominance of carpenters in the construction of medieval buildings, including mills, meant that stone structures were costly alternatives to timber-built mills. Interestingly, most illustrations of windmills in medieval manuscripts show post mills, although tower mills are depicted on a small number of later medieval church wall paintings and stained glass windows.

Medieval watermill from a late 13th century manuscript showing an undershot waterwheel driving a single pair of stones (Drawing S. Buckland, Mills Archive Collection, JSPB-ODR-403-141)

| From documentary evidence it appears that animal-powered mills were never as numerous as water or windmills. Nevertheless they were a useful, indeed sometimes long-term alternative, convenient in towns and castles and, it seems, particularly suitable for grinding malt for brewing. The number of horse mills appears to have increased in the wake of the Black Death in the late 1340s, which left more than a third of the population dead. They were cheaper and easier to build and maintain than wind or watermills, although fodder for the horses was more costly than water or wind. All mills were an important source of income in the medieval period. This is particularly highlighted by documents that refer to soke or suit of mill, that is, the right claimed by a lord through a mill for grinding all the corn which was used within his manor. This right was a privilege rather than statutory law and not all tenants were compelled to use the lord’s mill, but the income from multure, that is the toll taken by the miller, was generally a profitable one and so suit of mill was often vigorously enforced. The term ‘grist’, meaning grain brought to a mill for grinding, is frequently used to describe corn mills and payment for the service provided by the miller was by toll, an amount taken in kind from each person’s grain. The proportion of grain taken by the miller varied with both time and location, from as little as one thirtieth to as much as one tenth, with higher tolls tending to be taken in the north of England. The importance of mills to the manorial economy is graphically illustrated in the early 14th century Luttrell Psalter, which depicts both a post mill and a watermill. A prominent feature of the watermill is its stout door with a lock and sitting on the tailpole of the windmill is a large guard dog with a spiked collar. |

| Milling was one of the main economic activities of the later Middle Ages, becoming an important and competitive service industry that extended beyond manorial and estate boundaries. Mill numbers reached a peak in the early 14th century, with an estimated 10,000 watermills and windmills in England. Yet it seems this number was not sustainable and a decrease in the number of mills was already apparent before the onset of the Black Death in the 1340s. The complete article is available here. |