| Mills are most well-known for grinding corn into flour. Over the centuries mills powered by wind, water and other power sources have been used for many other types of industry. These series of newsletters will highlight a different use each month. You can find the full set here at https://new.millsarchive.org/2020/06/25/mills-make-the-world-go-round/. |

Colour mills

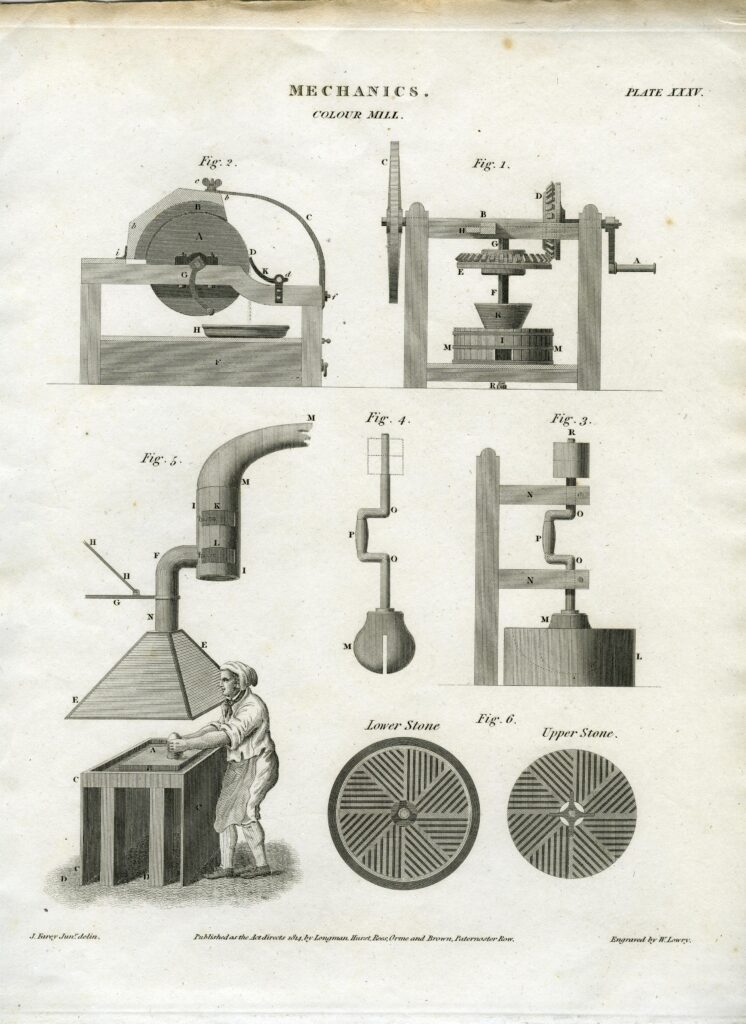

| A variety of mills and milling techniques have been used to produce the various ingredients that make up paints and dyes. Lead mills crushed white lead, used to make paint opaque, while paint or colour mills crushed other materials to produce pigments, using both horizontal and edge-runner stones. Dyewood mills ground woods such as logwood and Brazil wood to produce dyes for cloth. The primary ingredient of paint was traditionally oil, produced in oil mills. To this white lead (lead carbonite) was added to make the paint opaque, followed by the pigments that provided the colouring, such as red lead (lead oxide), made by roasting white lead. |

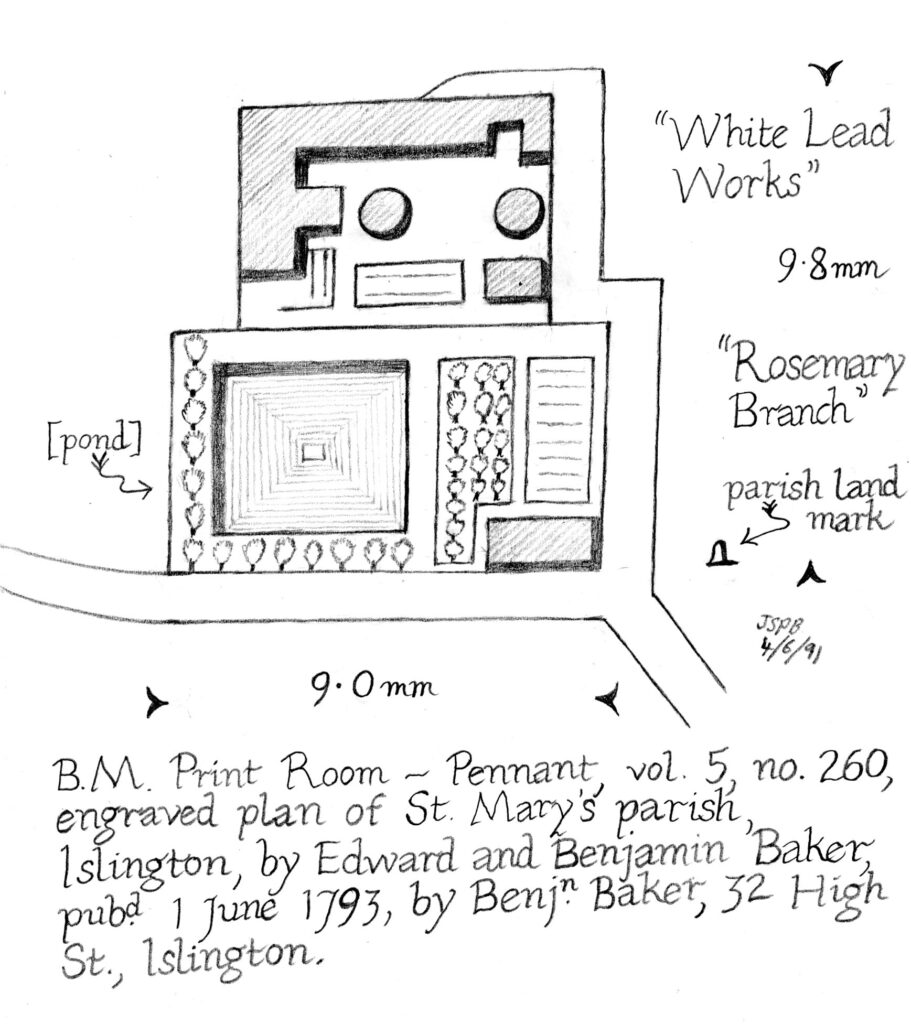

White lead was produced by a process developed by the Dutch. Metallic lead was placed in pots over acid, immersed in spent tan and placed in a brick chamber for 10-12 weeks. After this it needed to be crushed in a mill. A major centre for white lead manufacture in the 18th-19th centuries was Newcastle upon Tyne, which had a number of wind powered white lead mills.

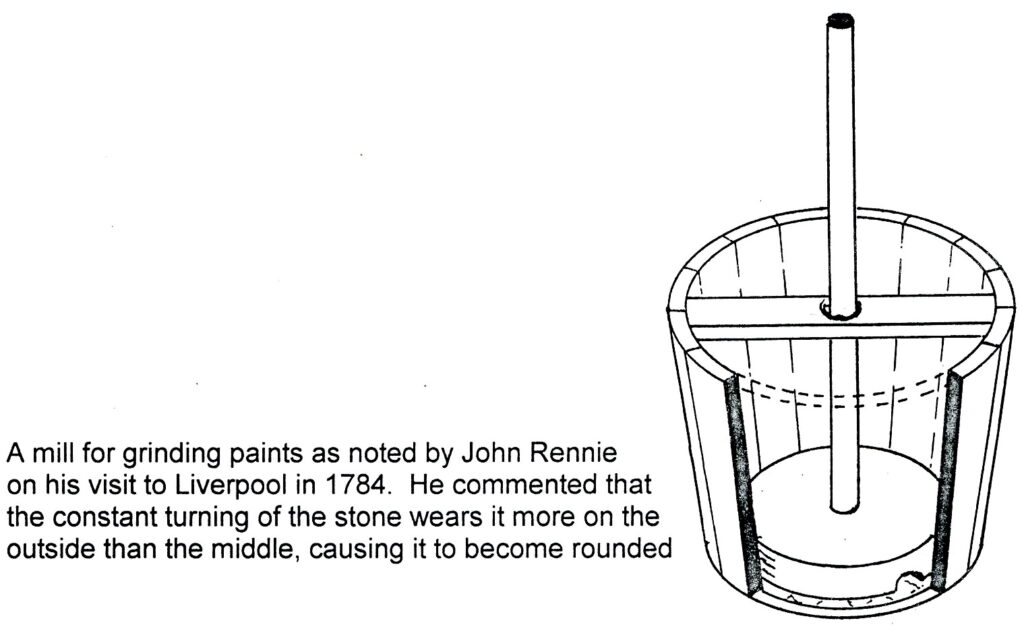

A variety of minerals could be used to produce the pigments used in paints. Wind powered paint or colour mills were found in Liverpool from 18th century; a description of a ‘mill for grinding paints’ in Liverpool is found in a diary entry from John Rennie from May 1784:

The machine has an upright shaft with a spur wheel on its lower end round which is a ring of tubs for holding the paints & to each of these tubs is adapted a spindle that turns a large stone in their bottom … the stone also has a semi-circular groove cut across below its middle to allow the paints to get in there. By the constant turning of the stone it wears more on the outside than the middle & at last it becomes of a circular form.

Plan of White Lead Mills near Islington – drawing by Stephen Buckland

Paint mill; photo by Roy Gregory

In some contemporary texts a distinction is drawn between ‘colour stones’ and ‘paint stones’ although it is not clear what this means. It could refer to the distinction between the horizontal stones in a tub described by Rennie and edge runner stones, used in some colour mills.

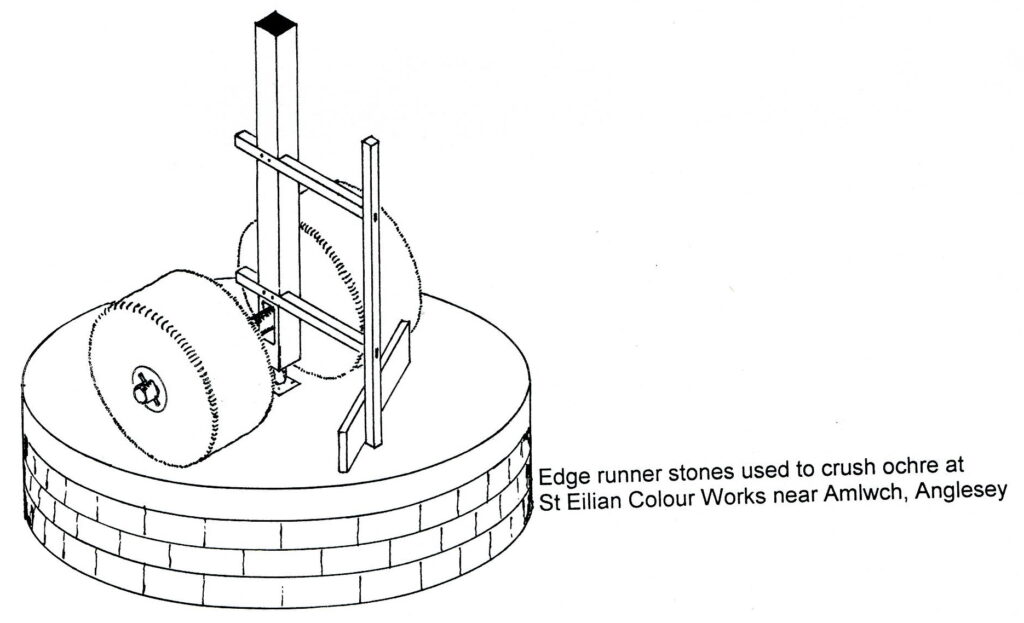

Ochre, a clay containing iron oxide, makes pigments with shades varying from yellow to red, depending on the amount of oxide present. The St Eilian Colour Works in Anglesey used ochre produced as a by-product from the copper mine near Amlwch.

Dyewood mills

| Dyewood mills produced pigments from wood. These were often located near ports, as the woods used were imported from overseas. The most common form of wood used was logwood, a tree in the pea family Leguminosae), imported from the West Indies and Central America. It gave a black dye, or with the addition of other chemicals, red, violet or navy blue. The other commonly used wood was Brazil wood (Caesalpinia echinata). This was imported from Central America, and gave its name to the country Brazil. It gave pink and red dyes. Other woods included: · Old fustic (Morus tinctoria) from Jamaica and South America – lemon yellow. · Young fustic (Rhus cotinus) – orange · Ebony from Jamaica – olive green · Cudbear, a lichen from the Canary Isles – peach-blossom pink |

Dyewood mills could process the wood in various ways. The chipper was a rotating circular plate with knife blades attached, which chipped away slivers of the wood. Chipped wood could be sold as it was, or powdered. Rasping barrels produced sawdust, used to dye wool before it was made into cloth. Fine powdered wood was produced with edge runner stones. The woods could also be ‘raised’ – fermented, to produce a dye which was more ‘fast’ (i.e. not so liable to run). This was done by sprinkling the chips with water and turning them occasionally until they became iridescent.

Diagram of a dyewood rasping engine (after John Smeaton), by Roy Gregory

| The development of synthetic dyes led to a gradual decline in the use of dyewoods. The last working water powered dyewood mill in the UK was the Albert Mill, Keynsham, which had been in operation since the 1870s. It dispatched its last load of logwood in 1964. |