| From Quern to Computer; a history of flour milling by Martin and Sue Watts covers a wide range of topics and this series of emails will summarise each one separately. | |

The application of animal and water power: From the Mediterranean to Britain

| The earliest milling tools were worked by human effort, using specially selected stones or wooden artefacts to pound, crush and grind various raw materials, including cereal grains. The use of animal power for turning millstones marked a significant step forward in the mechanisation of the milling process. It enabled the use of larger millstones with a corresponding increase in efficiency and output | |

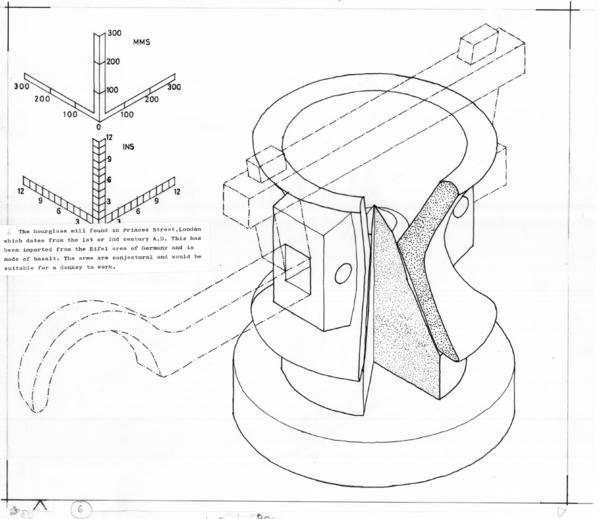

| The earliest and best known form of animal-powered corn mill is the hourglass type, sometimes referred to as the Pompeiian mill. The mill was turned by a mule or donkey attached to the stone by a timber yoke, the animal walking in a tight circle around it. Some smaller versions were probably turned by slaves. The Pompeiian mill appears to have been invented in the central Mediterranean area between the 6th and 4th century BC. The earliest reliably dated examples are those from the 4th century BC and by the 3rd century BC they were in use in bakeries around the central Mediterranean. They spread further north into Spain and France and a small number of examples have also been found in Britain. |

One, now reconstructed in the Museum of London, was found below Princes Street, London, in the 1920s.

Cut-away drawing of the Pompeiian type mill from Princes Street, London (Drawing J. K. Major, Mills Archive Collection, JKMC-DRW-23-007 JKM)

| Circular buildings, such as those found at Roman villa sites at Langton, Malton, North Yorkshire, first excavated in the 1920s and more recently at Ingleby Barwick, Stockton on Tees, may also have housed animal-powered mills. At both sites other buildings for grain storage and processing, such as threshing floors and grain drying kilns, have also been identified. The earliest water-powered devices are thought to date from about the middle of the 3rd century BC, at about the same time as the Pompeiian type animal mill was becoming more widespread around the central Mediterranean. There are basically two forms of waterwheel, defined by the plane in which they turn. The horizontal waterwheel is thought to have originated in Byzantium and the vertical waterwheel in Alexandria, both at about the same time. The often-quoted epigram by Antipater of Thessalonica written c.20BC-AD10, describes a watermill for grinding grain in poetic terms. His words suggest an overshot waterwheel driving millstones through gearing, so freeing the grinding girls from their toil. |

leaping on top of the wheel (SWAT-009)

As well as water-driven millstones, Pliny the Elder (AD23-79) implies that water-powered pestles were used in Italy in the 1st century AD for hulling and pounding grain (Natural History 18.23). Other literary references to milling in classical sources indicate a growing familiarity with such technology, the millstones being powered by human muscles, animals or water. Diocletian’s Edict of AD301 set down the prices of a watermill, horse mill, donkey mill and hand mill and later in the 4th century the agriculturalist Palladius considered that watermills made both animal and human effort unnecessary and suggested using the outflow of water from baths to drive waterwheels (On Agriculture I.41(42)).

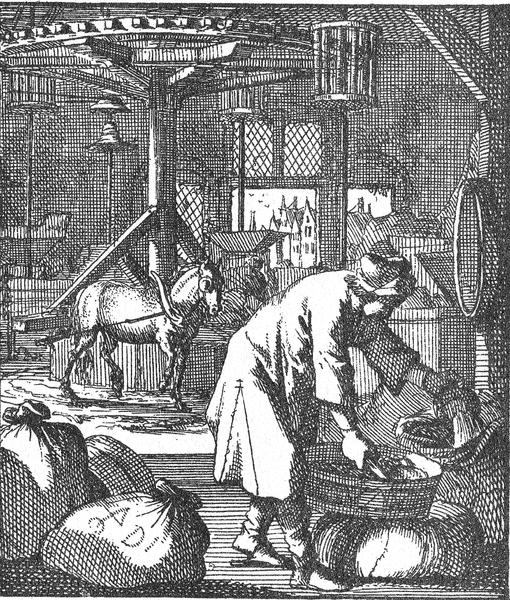

Dutch woodcut of a 17th-century horse mill (from 100 Verbeeldingen

van Ambachten, J & C Luiken, Amsterdam, 1698, MWAT-042)

| A number of other vertical-wheeled mill remains have been found by archaeological excavation throughout Europe and from evidence gathered it appears that Roman waterwheels were relatively low powered, perhaps no more than 1½ to 2 horsepower (>1.5kW) on average, capable of driving a single pair of millstones. In France, the building date of the remarkable milling installation at Barbegal, near Arles in Provence has recently been re-assessed, placing it in the 2nd century. Here two rows of eight mills were built down the steep slope of a limestone ridge. Water was brought to the top of the site by aqueducts and fed onto a series of overshot waterwheels, each taking water in turn from the one above. It has been suggested that Barbegal may represent a municipal rather than an imperial monument, built to supply flour to the citizens of Arles. | |

(MWAT-007)

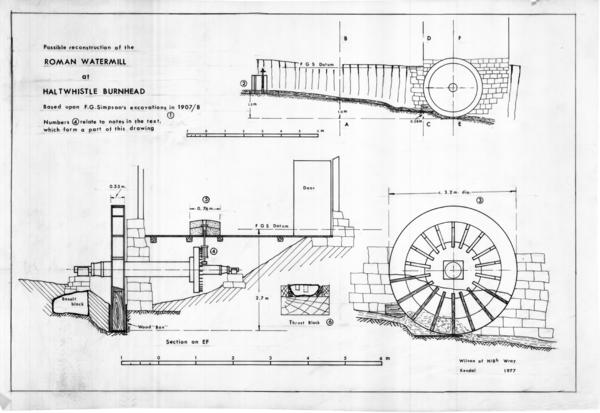

| In the second volume of History of Corn Milling (1899), Bennett and Elton offered no evidence to support the theory that the Romans had brought the watermill into Britain, but suggested it was a later introduction which was widely used by the Anglo-Saxons, based on the evidence of Domesday Book. Within ten years of this statement, the archaeologist F. Gerald Simpson excavated a Roman building at Haltwhistle Burn Head, to the south of Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland, which he interpreted as a watermill dating from the 3rd century AD. |

(Drawing P. Wilson, Mills Archive Collection, PNWC-DRW-28-031)

| In the south of the country, two sites of Roman watermills, at Ickham in east Kent and Fullerton, Hampshire, have been excavated. The most recent discovery was made in the aftermath of the severe flooding suffered in the area around Cockermouth, Cumbria, in 2009, on the banks of the river Derwent. Stone foundations and fragments of a timber structure that supported a waterwheel were found, broadly dated from coin and pottery evidence to the 1st or 2nd century AD. The earliest known horizontal-wheeled mill is thought to be that at Chemtou, the former Roman site of Simitthus in western Tunisia. Here a masonry structure containing three horizontal waterwheels was built into the remains of a collapsed Roman bridge across the Medjerda river. The mills are thought to have been built soon after the collapse of the bridge in the reign of Constantine, in the late 3rd or early 4th century AD, and to have gone out of use after a working life of 20 to 30 years. No information concerning the ownership of the mills – whether they were built to serve the army or the civilian settlement attached to the nearby quarries, or perhaps the imperial estates in the Mejerda valley – is available, but the multiple installation suggests an intended output in excess of purely local requirements. The waterwheels at Chemtou have been described as a ‘helix-turbine’ type, using both pressure and the kinetic energy of the water. Some doubts, however, have been cast on the Roman date attributed to the mills as the sophisticated water supply arrangements, with the waterwheels rotating in close-fitting stone-lined shafts, has no parallels until the later Middle Ages. The only closely comparable installation, currently undated, was discovered at Testour (Tichilla), further down the Oued Medjerda towards Tunis, in 1993. |

| Archaeological finds from Europe indicate the dominance of vertical-wheeled mills and in Britain similar evidence of Roman watermills suggests that they had undershot waterwheels between 2 and 3.6m in diameter. By way of contrast horizontal-wheeled mills became more common in the succeeding Anglo-Saxon period. The complete article and a select bibliography are available here. The next email in this series will cover early medieval mills and milling. |