| From Quern to Computer; a history of flour milling by Martin and Sue Watts covers a wide range of topics and this series of emails will summarise each one separately. The first milling stones Cereal grains form the staple food of many societies but such grains cannot easily be digested by humans until their hard outer cellulose shells have been broken up or removed. From earliest times this has been achieved by breaking open the grain between two stones. The first milling stones were hand-operated and are generally known as querns, a word derived from the Old English word cweorn. Most querns are made from stone, hence ‘quernstone’, but other materials have also been used, such as sun-dried mud coated with bitumen or wood studded with pieces of iron. Where no locally suitable stone was available, they were obtained from further afield. In Britain querns from the Prehistoric and Roman greensand quarries at Lodsworth in West Sussex have been found as far afield as Gloucestershire and Northamptonshire and, from the Roman period onwards, lava querns were imported from Mayen and Neidermendig in the Eifel Mountains of Germany. The beginnings of cereal cultivation led to, or were caused by, the adoption of grain-based subsistence strategies and a growing reliance on cereal-based products. This led to the development and increasing use of the oldest specific milling tool, the saddle quern. |

A saddle quern comprises a flat or dished slab of stone and a hand-held upper stone which is rubbed to and fro across it. Saddle querns were sometimes used in conjunction with mortars, in which grain was first pounded to remove the husks, but the flatter grinding surface of the lower stone was much more effective than the mortar for grinding grain sufficiently finely to obtain the maximum release of nutrients.

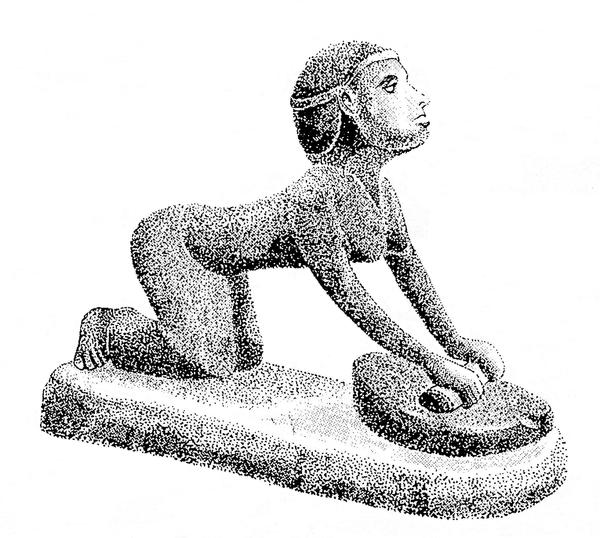

The saddle quern was generally worked on the ground, with the operator, usually a woman, kneeling behind it. It was hard work, the user needing to exert enough pressure with the rubber to break open and reduce the grain to meal. The saddle quern is the mill referred to by Moses in the Old Testament and upon which Samson was made to grind in the prison house (Exodus 11.5, Judges 16.21).

From ancient Mesopotamian texts, throughout the Bible to the writings of historians such as William Harrison (see later), documentary and ethnographic evidence indicates that grinding foodstuffs on a quern is generally considered to be the work of women, slaves and prisoners. Of course, there are exceptions. All male enclaves such as armies and monasteries had their own querns and men also used querns to grind other materials such as ochre and, in due course, tobacco.

‘The maid-servant that is behind the mill’. Grinding grain on a saddle quern, after an Egyptian statuette. (Drawing by Martin Watts; MWAT-004)

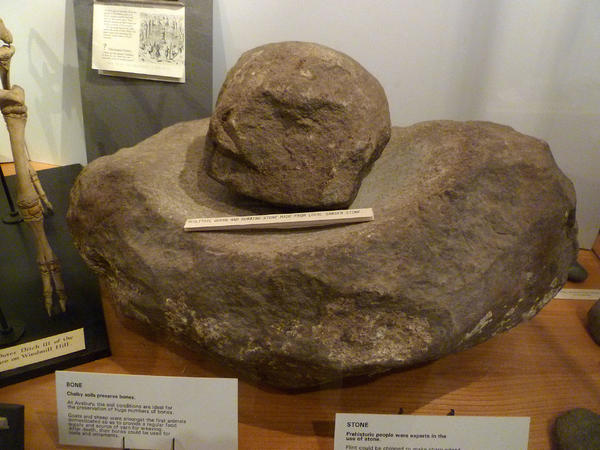

Saddle querns have been found on some early Neolithic sites, such as the causewayed enclosures at Windmill Hill near Avebury in Wiltshire and Etton in Cambridgeshire. They vary greatly in form from neat saddle-shaped stones, which give the tool its name, to chunky bowl shapes and large trough-shaped lower stones.

The saddle quern was the main means of grinding grain in Britain for some 3,500 years but in the Middle Iron Age, c.400BC, a new form of milling tool, the rotary quern was introduced. Dating evidence suggests that it was first used in southern England, gradually spreading north and west to reach Scotland, Wales, Ireland and Cornwall by the first century BC.

Neolithic saddle quern from Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure, Wiltshire (Photo M. Watts; MWAT-005)

| The rotary quern comprises two circular stones, one of which is rotated above the other by means of a projecting handle. Grain is fed into a central hole or eye through the upper stone and ground between the faces of the two stones. Comparatively easier to use than a saddle quern, it was also more efficient. It could also be turned by two people working together, again usually women, making a chore a more companionable task. The rotary quern was quite literally a revolution in milling technology and the principle of milling by turning one circular stone above another was to hold throughout the future development of milling with stones. |

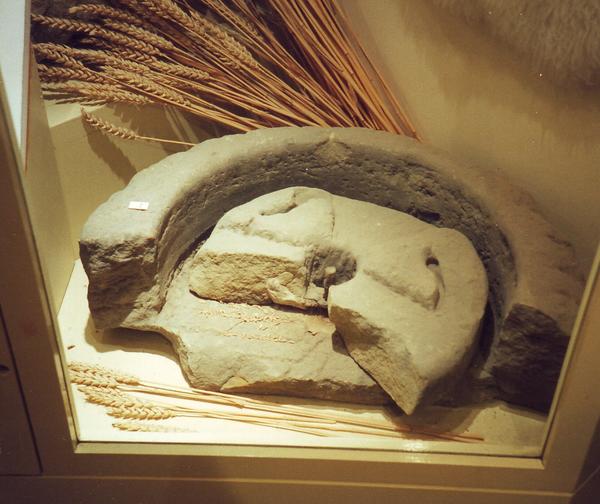

Iron Age rotary quern from Hunsbury Hillfort, Northamptonshire (Photo M. Watts; MWAT-006)

| Iron Age rotary querns in Britain comprised two thick, heavy stones, sometimes referred to as ‘beehive’ querns from the distinctive shape of the upper stone. They vary greatly in size from about 260 to 380mm diameter. Several different regional forms have been identified and it is noticeable that those from the south generally have sloping grinding faces and wide eyes with a handle hole in the side or a slot across the top, whereas those from the midlands and north, including southern Scotland and Ireland, have narrower eyes and flat grinding faces, with one or more handle holes in the side. |

The upper stone of a Romano British rotary quern from Probus, Cornwall

| Although beehive querns continued in use during the Roman period, rotary quernstones generally became larger in diameter and thinner with wide eyes. The grinding faces, which were flat or slightly sloping, were often dressed with a pattern of furrows similar to that used later on millstones. Their design, which shows great variety, was probably influenced by the querns of German lava which were imported on the heels of the Roman invasion in AD43. Indeed the Roman army brought such querns with them in their baggage train. In the medieval period the use of querns was widely prohibited as many manorial tenants were compelled to have their grain ground at the manorial mill, which could be some distance away, and to pay a toll for the privilege. Not surprisingly, some preferred to use their own querns and manorial accounts frequently contain references of fines for those not taking their grain to the lord’s mill. Freemen could use their own querns and special licenses were sometimes granted. Establishments such as castles and monasteries often had querns in their kitchens. |

Medieval pot quern from Rievaulx Abbey, North Yorkshire (SWAT-004)

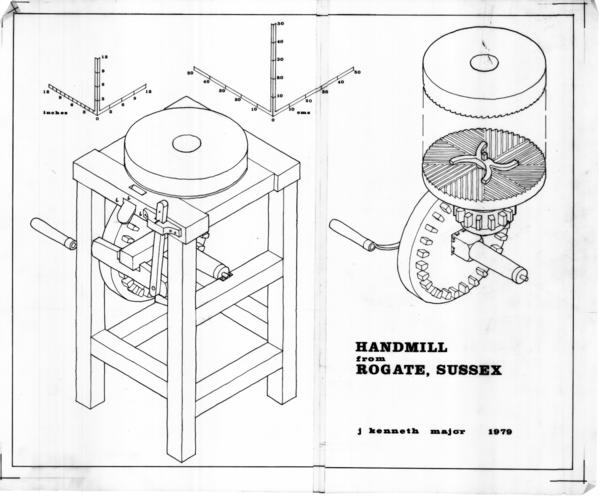

A new form of rotary quern, the pot quern, came into use in the Middle Ages. This derives its name from the shape of the lower stone which has a circular recess within which the upper stone turned, the ground meal being expelled through a spout cut through the side of the lower stone. Pot querns vary greatly in design, demonstrating much individuality. In the post-medieval period rotary querns continued to be used in the home, mainly for grinding small amounts of malted grain and mustard seed. Writing in 1587, William Harrison tells how his wife grinds ‘good malt upon our quern’ to save paying a toll. The final development of the rotary quern was a handmill in which a small pair of millstones was mounted on a timber frame, the upper stone being turned by a handle through a pair of gears. |

In 1898 Bennett and Elton wrote that the quern ‘virtually only exists as a relic of antiquity in the cabinets of the curious’. But that is not the end of their story, for querns were to remain in daily use in the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland and in Ireland into the 20th century where they were not only used for preparing porridge but also for grinding barley for that illicit drink, poteen. And, like the saddle quern, they are still used in parts of the world today.

Geared handmill from Rogate, West Sussex (Drawing J. K. Major;JKM-DRW-26-001)

The complete article and a select bibliography are available here. The next email in this series will cover the application of animal and water power: From the Mediterranean to Britain. |