| This week is Volunteers’ Week, and to mark it we’d like to say a HUGE thank you to all our wonderful volunteers, who have stuck by us despite the pandemic. We have sorely missed their friendly faces in the office, not to mention all the help they offer in working through our collections and enriching our online resources. While we were unable to have volunteers coming to the office in person, and had to content ourselves with ‘coffee break’ catch-ups via zoom, we gave a lot of thought to finding ways that volunteers could still assist us in working on our collections from the comfort of their homes. In this newsletter you can read about how this led to our latest initiative, “Archiving at Home”. |

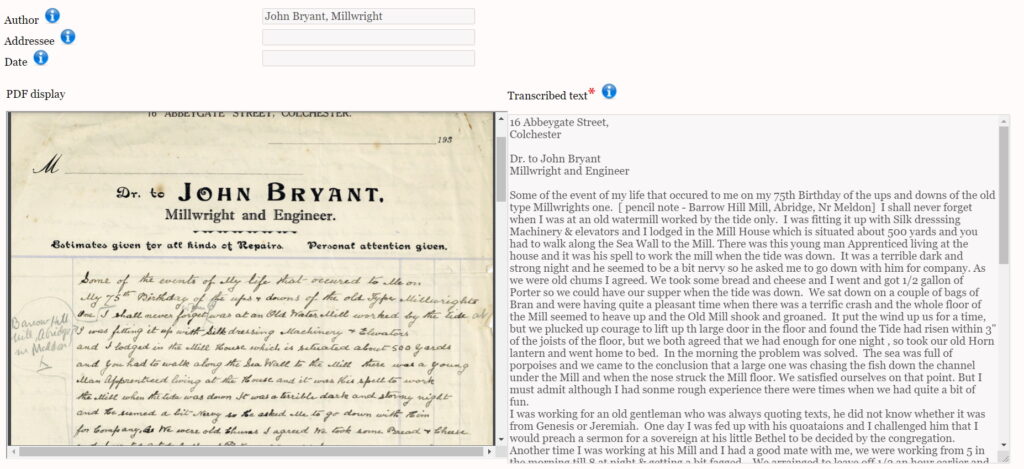

| Archiving at home Last October we submitted an application to the Archives Testbed Fund to build the “Archiving @ Home Hub”. The fund is a resource provided by the National Archives to enable archive services to explore new ideas. The emphasis is on trialling new approaches to archives work and experimentation, with the success of the specific project less important than sharing lessons learnt. In January we were delighted to hear that we had received a grant to build the Hub. Our idea was for an online facility where volunteers could log in and complete different tasks. Initially we have focused on transcribing text documents in the archive. This converts an image of a handwritten or typed document such as a letter or notebook into searchable text that can be uploaded to our catalogue, making it easier for people to find the information contained in the document. |

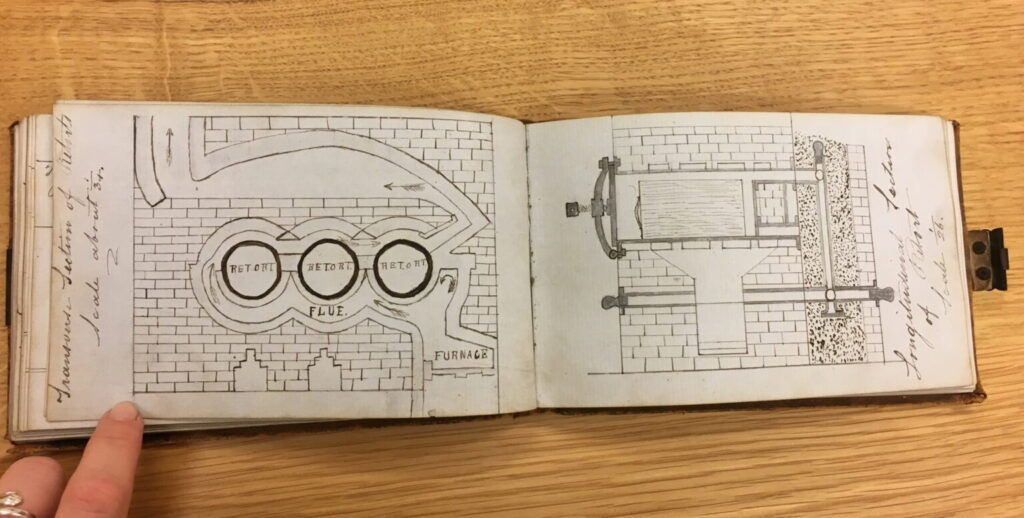

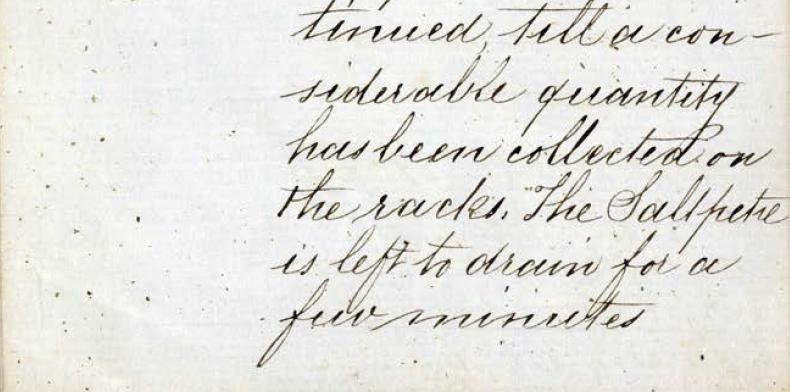

| Our expert IT consultant Paul designed the site, and at the end of March we announced the project on social media and asked for volunteers to help us test the site. A number of people signed up, including existing volunteers and new additions. You can read about some of their experiences below. We have now finished testing and are ready for more volunteers to get involved. If you would like to help, please contact me via archivist@millsarchive.org. Transcription #1: What on (or in) Earth is Saltpetre? Mary Gregson March marked about a year since my archive volunteer projects were put on hold due to the pandemic. I hadn’t been idle, I’d applied for and been accepted to do a master’s in Archives and Records Management, which was and still is keeping me busy, but I was restless. I am very grateful for my learning, but I missed doing something for archives. So, it seemed like fate when at the beginning of March 2021, I saw The Mills Archive were asking on Twitter for people test the ‘Archives @ Home Hub’. I instantly felt that buzz of excitement that I used to feel when I woke up to a day of archive volunteering. I replied to the tweet and sent an enquiry form (I was determined) and after a couple of exchanged emails I had an account and was assigned my first document to transcribe. Which was an 1871 notebook from the Waltham Abbey Royal Gunpowder Factory, which describes the processes carried out in the mills. |

| Having done a little bit of transcription before (The Highlands and Islands transcription project) I was aware that I not only enjoyed transcription, but also the journey of overcoming the problems that inevitably arose from it. It is this journey that I’d like to describe, because at some points it’s interesting, some points frustrating, often funny in hindsight and always a learning curve. The problems, I think, arise mostly from three points: 1. My own instinct 2. Gaps in knowledge of the industry/time 3. Handwriting Now, I’m quite good at checking my instinct and reasonably familiar with 19th century handwriting but I know nothing about milling and nothing about gunpowder, so I thought I had my weaknesses in check. But as it turns out, I had to fight my instinct first. |

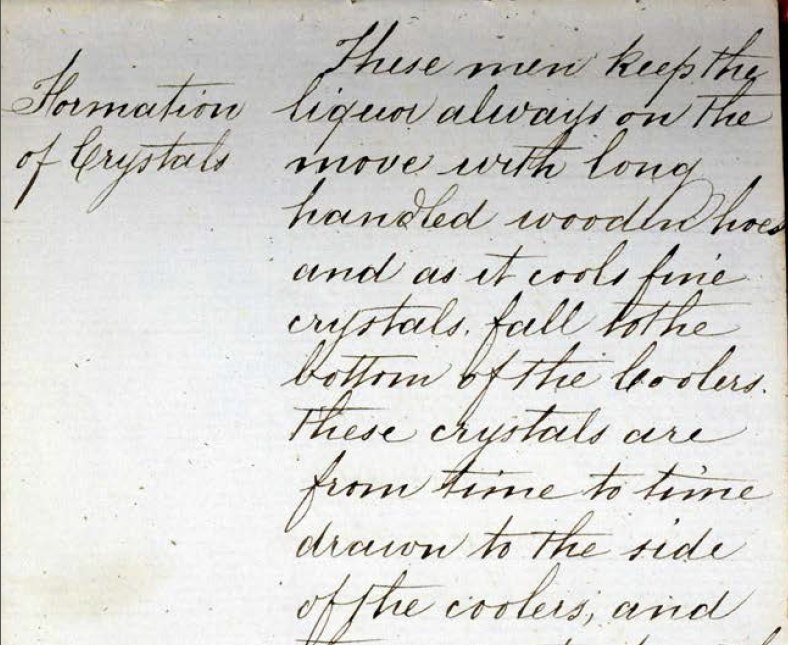

One rule of transcription in that the words must be transcribed as seen. Spelling mistake? Transcribe it spelt wrong. No punctuation? Put none there. My problem was capital letters, seemingly random. In the first section the word ‘cooler’ appears three times.

The first time as ‘Coolers’ and my instinct thought the second time as well, I wrote it with a capital. Luckily as much as my instinct was working against me, it was also working with me and I knew something wasn’t right. My eyes flicked back to the document and I saw the word as it was, with a ‘c’. This rule is one that becomes a kind of habit as you get further into the transcriptions and get used to it, but at first it does take some getting used to. Plus, once you’ve identified a rogue capitalisation then you’re always ready for more.

| My next challenge was both handwriting and lack of gunpowder knowledge. Imagine looking at a word that you don’t know exists and that is written in beautiful, curly, slanted 19th century script. It was time for detective work. I guessed it was an object, and important because it was in the middle of a sentence and started with a capital S. I figured that the best thing to Google was ‘how was gunpowder made’ (the sensible part of me was a bit nervous about this being in my search history without context). I was lucky, the first thing that came up were three elements that earlier Chinese alchemists used, one of which was saltpeter (spelt Saltpetre in the Waltham Abbey document). Detective work complete, I appreciated my luck, Poirot never worked things out that quickly, and I thanked Google for its existence. Just to double check I typed in Saltpetre and after a bit about curing meat, Britannica.com confirmed that it was otherwise known as potassium nitrate, was formed in certain soils and, most importantly, that there was a demand for it as an ingredient in gunpowder. I was now certain that this was my mystery word. It is these small challenges and the subsequent (hopefully) victories, that I’d like to document in a mini-series about transcription. It is something that I and surely many others love to do and something that has the possibility to take the transcriber on a journey, not just deciphering handwriting, but learning, in this case about milling and gunpowder manufacture. I find it wonderful to think that with material in archives all over the world, the possibilities are endless. The ‘Archiving @ Home’ Volunteering Experience Kira Hollebon I’m a second year Museum and Classical studies student from the University of Reading and my aim throughout the year was to secure a volunteering role to gain the necessary skills required for a future career. I knew this was going to be difficult as the pandemic had closed many organisations and many were currently not offering jobs, but I was absolutely determined to find a role that I would love. I came across the transcribing role through my brilliant careers mentor. A mentor would be assigned to a student to give advice and help relating to life after university. As fate would have it, my mentor (Liz Bartram) works at the Mills Archive Trust, and mentioned that they were producing an online platform to transcribe documents remotely by volunteers so it is accessible to a wider audience. I jumped at the opportunity! I’ve always wanted pursue a career related to curating, archiving and conservation as I love learning about the past and how to conserve historical objects, so this role is absolutely perfect. I’m sadly not able to see the amazing staff in person, but I’m truly thankful for the support I’ve received from both Liz and the Mills Archive staff! |

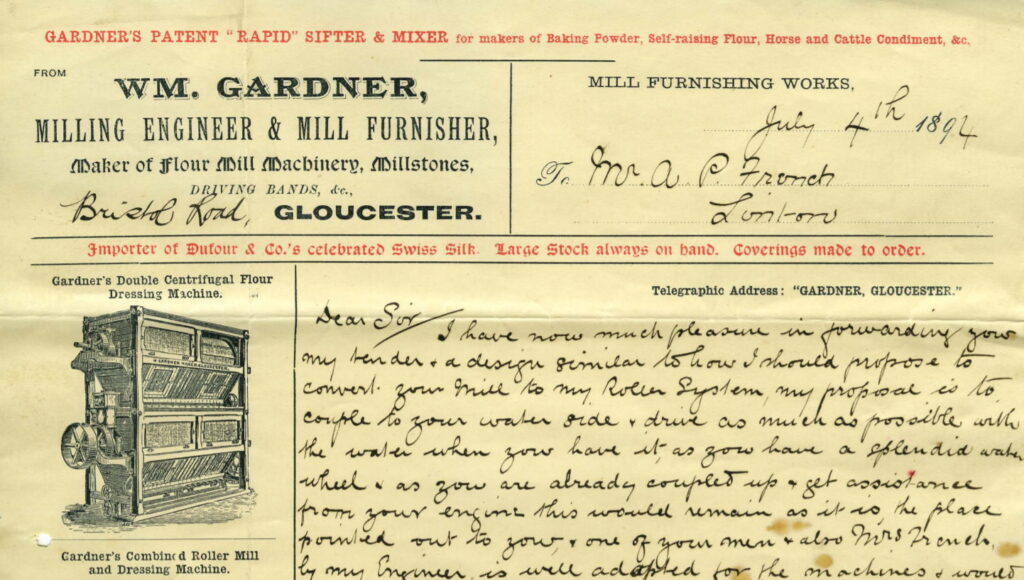

| The first document I transcribed was an 1894 correspondence letter regarding a new Roller Plant at the Hildersham Mills. I was initially nervous because I’m new to transcribing and I don’t really have any knowledge on Mills, but I was intent on doing it right. One of the rules of transcribing is to type down any mistakes, abbreviations and capital letters. Even if I knew the spelling was wrong, I had to transcribe it that way, which went against every bone in my body. The handwriting was difficult to understand, but as I got into the groove it started to become very familiar. Despite this, it gave me a new found love of transcribing. It has a special art to it as you start to understand the document in more detail and each one has a personal touch to them. Overall, I’m thoroughly enjoying taking part in the ‘Archiving @ Home’ project. It has improved my CV and given me experience and knowledge that would appeal to an employer. I love that documents like these are becoming more accessible, so more people have the chance to appreciate what museums and archives have to offer! |