Incense is made from tree resin, roots, flowers or seeds and produces a sweet smell when burnt. It has been used widely throughout the world in religious ceremonies.

In China incense was manufactured in watermills – often three or more on a hillside. Small wooden waterwheels powered millstones or hammers to crush the wood.

A traveller in China described the process in a National Geographic magazine of 1937:

Coming upon a crude dam of cobblestones, we inferred that it diverted water for irrigation.

But as our party entered the village of Tungtacheng, we saw that the “irrigation” channel was a millrace for the only industry which we came upon in all our travels around Peiping (now known as Beijing) that used the wealth of potential water power. Tungtacheng manufactured Chinese incense.

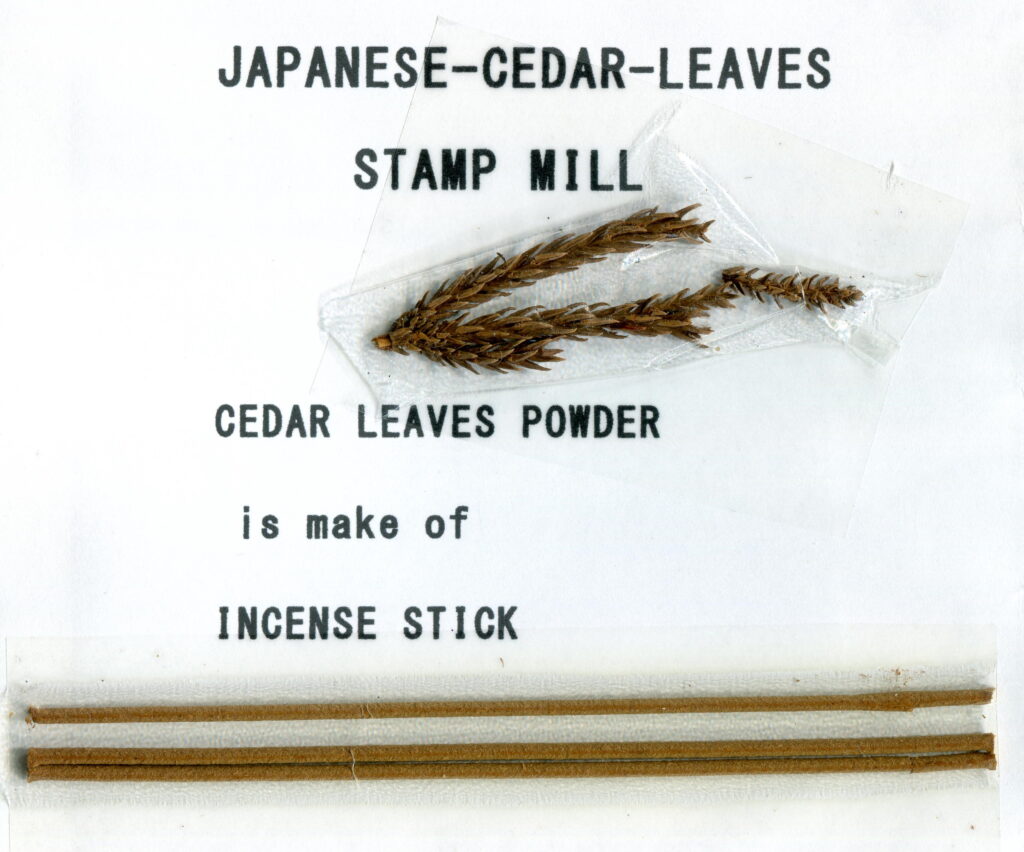

Incense is made up entirely of plant materials, the chief constituents being elm and cedar powder. Citizens of Tungtacheng grind branches, roots, and bark of the elm and cedar between large grind stones operated by water power. The milling process resembles flour making. Elm powder supplies the binder for incense and also gives body to it. The cedar powder spreads a pleasant fragrance through the room as the incense burns.

We looked in at the building where they sift cedar and elm powders to remove unground particles or foreign matter. A worker sat on a stool, his feet on a rocker, raising first one foot then the other. A shaft transformed this patient effort to a sieve enclosed in a canvas-covered frame. Water is then added to the dry powders of elm and cedar, this is then stirred into a dough-like mass, the consistency of putty. The next step requires a wooden cylinder, closed at one end save for a hole three-eighths of an inch in diameter, and a plunger to fit into the cylinder. After the device has been filled with the mixture, it is operated on the principle of a grease gun. This is then forced out to produce the incense sticks which are then dried.

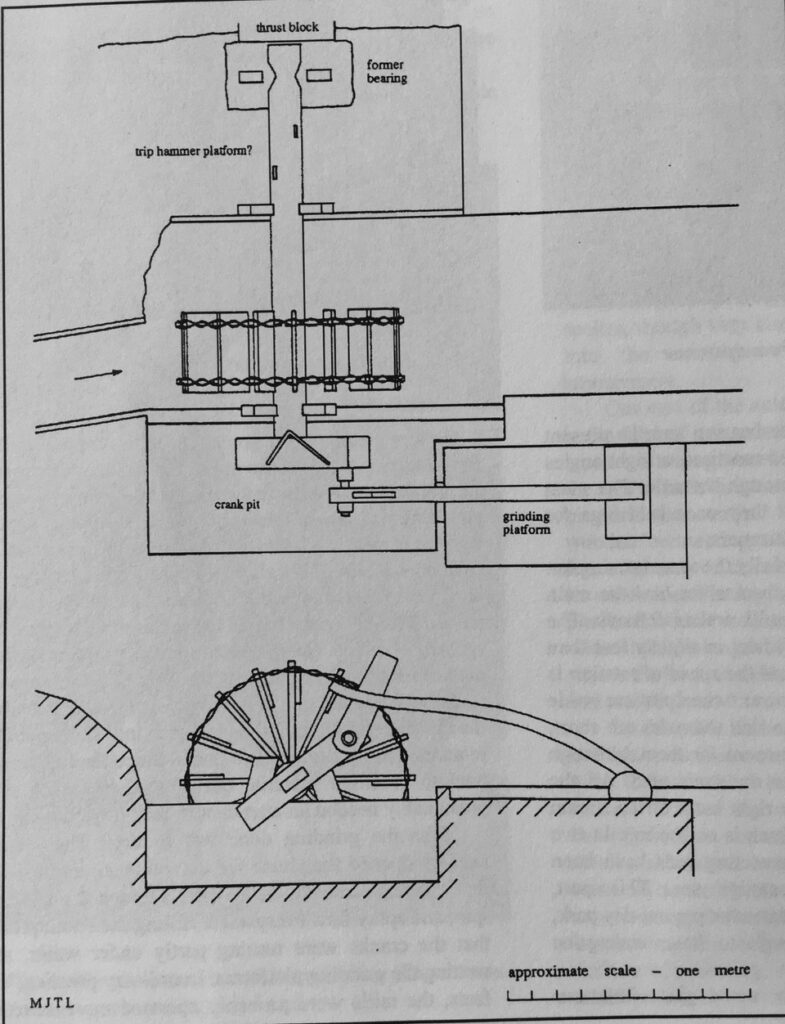

An article in International Molinology in 1996 described a visit to Tianhe Park, Guangzhou China and is illustrated with photographs of three mills coming down the hillside and a ground plan of the upper of the three mills.

It shows a series of very small waterwheels with crank pits and grinding platforms. The topmost mill has a waterwheel just over a metre in diameter and crudely made of sixteen pairs of radial wooden spokes carrying paddle boards and linked circumferentially by twisted thongs of bamboo. The wheels were undershot. One end of the wheel shaft carried an overhung crank arm in the form of a massive square timber held in place by an oblong tenon with iron clamps.

Thanks and acknowledgment go to Mike Lewis and his wife for allowing us to use their images and drawing of the mill.

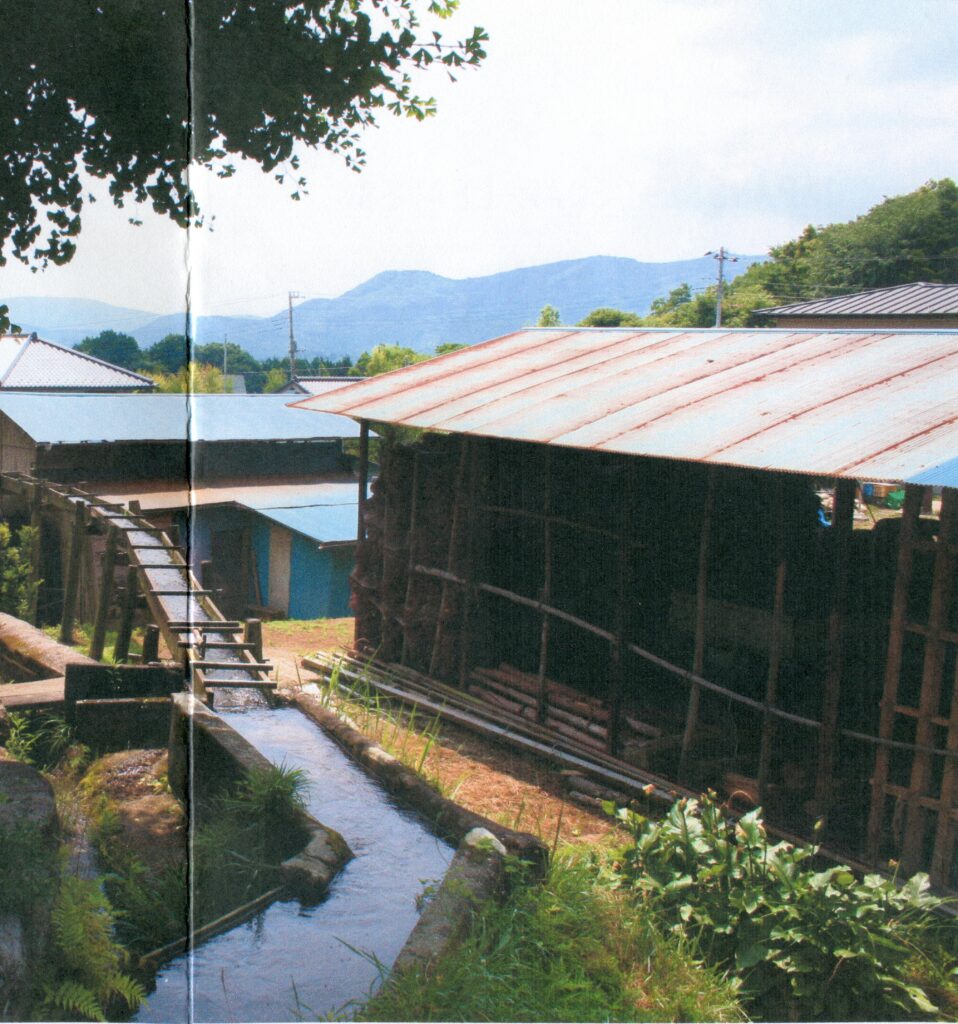

Japan also had a huge incense industry, using waterpower to crush the Cedar leaves.

Acknowledgement to Mr. Kawakami for the illustrations.

These mills continued to work into the 20th century, but eventually fell out of use when electricity replaced water power.