Sybilla Righton Masters can lay claim to being the first person living in the American colonies to be awarded an English patent – two in fact, and possibly the first female machinery inventor in America. Of course, as a woman these patents could not be registered in her own name but in that of her husband Thomas.

The second child of Quakers William and Sara Murrell Righton, Sybilla was possibly born in Bermuda, where her parents married but certainly grew up in the family plantation at Burlington, West New Jersey, on the banks of Delaware, where her father was a mariner and merchant. At some point between 1693 and 1696 she married Thomas Masters, a prosperous Quaker merchant and moved with him to Philadelphia.

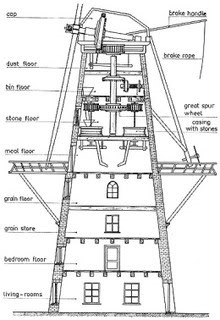

Patent drawing for corn mill

This remarkable woman, as well as raising four children, exercised a remarkable talent for mechanical invention, creating a corn processing mill that produced a corn meal she called Tuscarora Rice.

Her mill pulverised corn rather than grinding it. At that time, the process for grinding corn used two large millstones. Sybilla however had seen American Indian women pound corn with wooden mallets. So, she followed on from this by inventing a mill that used hammers to make cornmeal, which was much easier than finding, hauling and using huge millstones.

Sybill and Thomas hoped, however, that they would be able to sell this cornmeal to the English market, but it did not catch on there. Perhaps the fact that “Tuscarora Rice” was falsely advertised and sold as a cure for tuberculosis meant it attracted the wrong market? However, it proved a huge hit in the colonies, becoming a staple in the south-eastern diet. This product is hugely popular to this day in the United States, known under the name of grits.

Sybilla wanted a patent for her invention so that she would have sole authority to sell the products. Unfortunately patents were not issued in Pennsylvania – not to be discouraged, she notified her Quaker meeting that she intended to go to London to apply to King George I’s government for a patent there and set sail in 1712. But again, she met with another stumbling block – the government did not have a regular governmental process for giving patents. Not to be beaten, she applied for a patent from King George himself.

Wheels turned extremely slowly – while waiting for an answer, Sybilla worked on another idea. She had invented a new fabric worked out of straw and the leaf of the palmetto tree, weaving them together into products like hats, bonnets and chair covers. Since she had been granted a monopoly for the importation of palmetto leaf, she applied also for a patent for her weaving method and opened a shop in London to sell these goods, at the sign of “the West India Hat & Bonnet, against Catherine-Street in the Strand” .

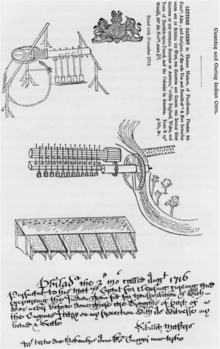

Letter of Patent for “Cleaning and Curing The Indian Corn”

It took 3 years before King George in 1715 finally awarded the patent for milling corn. But, what seems extraordinary in modern eyes, it was not granted to Sybilla –it was given to Thomas, for “a new invention found out by Sybilla, his wife”.

The following year, the King gave Thomas a patent for Sybilla’s weaving method “in such a manner as was never before done or practised in England or any of our plantations”.

Thomas and Sybilla returned home to Philadelphia, and in 1717 Thomas petitioned for recognition of his wife’s British patents, which were then reissued in her name, since Pennsylvania was now approving its own patents. Sybilla died in 1720.

Described in a recent blog on early American colonials as “a woman out of her time”, Sybilla, as well as being the first person to patent an invention there was the only woman there, to have patented an invention until 1793 when a mill owner’s wife Hannah Wilkinson Slater was issued a patent for a cotton thread. But that’s another story.

Sources

Blog – 18th Century Colonial and Early American Women- Barbara Wells Sarudy

The Monstrous Regiment of Women -A Women’s History Daybook – Sharon L Jansen