While sat in a meeting in our Founders’ Room, my eyes travelled across the spines of the antiquarian books visible from my seat, and I couldn’t help but notice a small, gold-decorated book covered in tan-coloured leather. The name of the book was too small for me to read from a distance.

After the meeting had finished, I decided to investigate, and was surprised to find a little book that at first glance did not seem relevant to milling. In fact, what it does is put milling into the wider social, economic and political context of early 19th-century Norway. Having previously not known as much about milling as I would like, and knowing even less about Norway, my knowledge on both has now significantly improved!

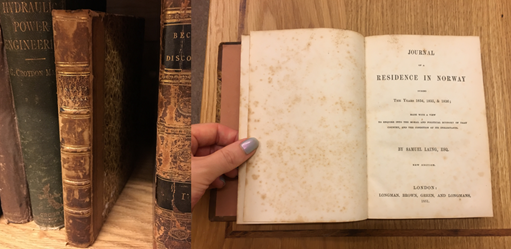

The spine declares the book to be “Laing’s Norway” in small gold lettering. On the first page the full title is provided: “Journal of a Residence in Norway during the Years 1834, 1835 and 1836: Made with a view to enquire into the moral and political economy of that country, and the condition of its inhabitants”.

The author, Samuel Laing (1780 – 1868) came from Orkney and was a well-known Scottish travel writer. He travelled throughout Scandinavia and northern Germany, and published works about his travels. His son, of the same name, was a railway administrator who wrote important works on religion and science, and became a Liberal Member of Parliament. I suspect that Samuel the Younger probably got some of his political leanings from his father, which become apparent in the book about the Elder’s Norwegian travels.

Our particular edition of “Laing’s Norway” was published in 1851, and was donated to the Mills Archive by the SPAB Mills Section. It is beautifully bound, and looks well-loved and well-handled! The pages are starting to come away from the spine, so this is a book to consider for future conservation and for limited handling. The chapters covers a wide range of subjects, such as: outfits and traditions of visiting Laplanders, diet and traditional dishes, winter scenery, potato brandy, state of the female sex in society, wildlife e.g. wolves, state of education, and hereditary attachments to the horse! And, of course, mills.

Norwegians, according to Samuel’s introduction, are “the most interesting and singular group of people in Europe”. They live under ancient laws and social arrangements unlike those that have grown up in feudally constituted countries. Samuel felt that Britain is honour bound to ensure that Norway remains independent as a nation, and that her liberal constitution is protected.

“The stream issuing from this snow turns a corn mill, which I went to examine while my pony was feeding”.

On 18th August 1834, Lang stumbled upon a corn watermill (p40). He noticed several things about this mill, and about Norwegian mills in general during his travels.

Norwegian mills were very distinctive in that they had horizontal water wheels (intriguing technology I have heard referred to at the Archive as “Norse mills” with examples to be found in Scotland). Samuel reasons that this technology (as opposed to using vertical wheels as in most British mills) helps to prevent the wheel getting clogged with ice, or hindered by back-water. The author notes that this design is similar to those used in the “Zetland islands” (Shetland Islands) but nowhere else in Britain has any quite like it.

According the Samuel, there are no restrictions regarding who can build and operate a mill. Every man has “Odel’s right”, which refers to one’s right to claim family property as it gets passed down. He observed that each little farm had its own mill.

Samuel was surprised, however, to see that such ingenious structures were made of such basic materials: “There was not a nail in the mill, which was all put together with wood, or with fastenings of birch bands made of twigs bruised and twisted together” (p42).

Laing observed the mill stones themselves, which he described as very small – similar to the size of Scottish quern stones – and made out of very hard gneiss. The stones were placed together very closely and moved very fast, which meant that the grinding of whole unshelled oats produced flour almost as fine as wheaten flour. Laing writes that the process of using the whole oat (rather than shelling it first as in Scotland) must be much more economical than the Scottish process, during which the most nutritious part of the oat is stripped out. The meal is excellent for making flat cakes, though he notes that they are not superior to the gentleman’s standard oatcakes of Britain!

Curiously, there are numerous references and descriptions of something called “bark bread” – on which Laing admits his views were altered as a result of his travels. Previously, when he had heard about grinding and baking birch bark during times of scarcity, he had laughed at the idea “of a traveller dining on sawdust pudding and timber bread” (p41)!

“Sawdust pudding and timber bread”.

It came to Laing’s attention during his journey that he saw many trees stood stripped of their bark, dead and whitened by the seasons, “mere ghosts of trees” (p219). This he attributed to the harvesting of their bark to make bread.

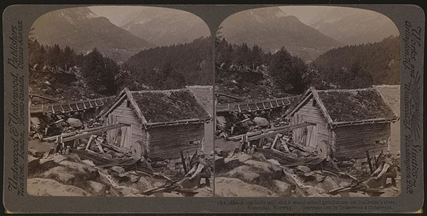

Bark bread is in fact made from the inner rind found next to the wood of the tree. This rind is taken off in flakes and steeped in water to remove its bitterness. The flakes are then hung on a rope to dry in the sun (or sometimes perhaps over a fire as the below image shows?) and would resemble sheets of parchment. Then once dry, the flake would be pounded into small pieces, mixed with corn and ground into meal on the hand-mill or quern.

Not only did the palatable quality of bark bread challenge the author’s assumptions, he was also surprised by the high use of such a food source, and wrote that many forests suffered much damage between 1812 and 1814, when war and poor crop yields combined to risk starvation for those who were not prepared to be resourceful with their meal for the mill.

While Laing admitted to the tolerable taste of the bark bread, if it was prepared well, he comments that it is a very costly way to feed oneself. “The value of the tree, which is left to perish on its root, would buy a sack of flour, if the English markets were open. They starve and we shiver in our wretched dwellings, although each country has the means of relieving the other with advantage to itself” (p220).

Fried fish for supper

And so ends our journey with Samuel Laing, for now at least. I like to imagine him on his pony, plodding across the dramatic Nordic scenery, with a few notebooks packed in his panniers, an emergency supply of potato brandy and bark bread, sometimes simply following his stomach.

“In the evening I reached this single farm-house, and got grass for my pony and quarters for myself; and the mistress gives me the comfortable hope, if I understand her right, of fried fish, which are still in the river, but which the mowers will catch in time for supper”.

I hope he got his fried fish supper.