Today is World Poetry Day, an event to promote and to “give fresh recognition and impetus to national, regional and international poetry movements”. An ideal opportunity, therefore, to show you some of our favourite mill-themed poetry!

Mills have long been the subject of romantic poems about England’s green and pleasant land. They represent a fondly-remembered way of life upon which people love to reminisce; countless poets have memorialised the quaint and simple landscape which once commonly displayed the iconic silhouette of a windmill, peacefully turning in the breeze.

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) was a Victorian poet and author, and the youngest to date recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize for Literature. He is best known for The Jungle Book, Just So Stories and Kim, tales set in India where he grew up as a young boy and then returned to as a young man in the army.

Perhaps under-appreciated, however, are the poems set in his native England. Kipling moved to Rottingdean, East Sussex in 1897, and his new home became a fresh source of inspiration for his writing.

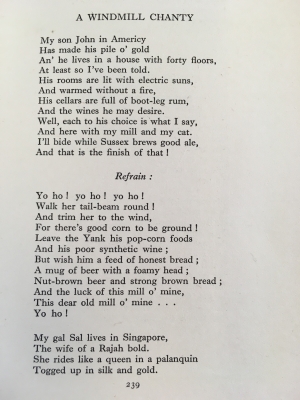

R. Thurston Hopkins’ book Kipling’s Sussex Revisited (available in the Mills Archive library) gives us such gems as A Windmill Chanty, with the refrain:

Yo ho! yo ho! yo ho!

Walk her tail-beam round!

And trim her to the wind,

For there’s good corn to be ground!

Leave the Yank his pop-corn foods

And his poor synthetic wine;

But wish him a feed of honest bread;

A mug of beer with a foamy head;

Nut-brown beer and strong brown bread;

And the luck of this mill o’ mine,

This dear old mill o’ mine…

Yo ho!

In this poem, the traditional windmill (likely a post mill, if the tail-beam he’s referring to is the tail pole) is juxtaposed with a description of modern, American-style living in the first stanza: a huge house, with electric lights and heating. Kipling (or at least the narrator of his poem) is eager to proclaim that he is eschewing such modern grandeur, and is happier living a simple, rural life:

Well, each to his choice is what I say,

And here with my mill and my cat.

I’ll bide while Sussex brews good ale,

And that is the finish of that!

It’s interesting how a windmill here is presented as the direct opposite of a contemporary, progressive lifestyle; as an alternative to the imposing threat of modernisation from a forward-thinking world.

Another poem of Kipling’s, A Ballade of Excellent Bread, is on a similar vein:

Ho there! Ho there! Millstones and mill!

Hearken well to my lay!

I will not eat pop-corn cakes,

Or grape nuts soaked in whey.

I will have no rice croquettes

Or buns of coconut shred;

But I will have the King of them All—

A jolly old loaf of bread.

Miller, miller, jolly and gay,

Grind me some of your best to-day;

Wholemeal flour branny and bold

Fill me as much as my bin will hold.

Waterwheel, waterwheel! Domesday Pet!

Stop and harken to me!

I will have no shredded wheat

And crucified flour for my tea.

I will have no wafers of rye;

But out of your golden hoard,

I will have some honest meal

To bake a loaf for my board.

Baker, baker, jolly and gay,

Thump and bang your dough to-day;

Drink up your pewter of barley-bree,

And magic a wheaten staff for me.

Again, Kipling seems very disillusioned with new-fangled culinary inventions such as pop-corn cakes, rice croquettes and coconut buns (delicious as they may sound!) and is keen to uphold the classic meal-time fair of ‘a jolly old loaf of bread’ baked from ‘honest meal’, ground by a traditional watermill.

Despite mentioning a watermill, the poem is accompanied with a drawing of West Blatchington Windmill (pictured above), now a Grade II* listed smock mill in the Brighton and Hove area. You can view Frank Gregory’s collection on our catalogue here, https://catalogue.millsarchive.org/west-blatchington-3 with several images of the mill, which is still standing today.

The idea of the watermill was perhaps inspired by Park Mill, on the estate at Bateman’s, where Kipling lived from 1902 until his death in 1936. The mill, powered by the River Dudwell, was not in operation during Kipling’s time, and instead he installed an electric turbine inside the mill to provide power for the house. It was restored however, in 1975 by the National Trust, with Frank Gregory as one of main influences in the restoration. It was put back into working order, and continued to grind happily until 2015, when the axle tree failed. This was replaced and work was started on the millpond in 2018, which hopefully should see completion, and the reopening of the mill, later this year.

The picturesque mill was well-loved and recorded by many mill enthusiasts, including Frank Gregory, Derek Ogen, E. M. Gardner and Arthur Lowe. Over 100 images of Bateman’s Mill/Park Mill are available to view on our catalogue here.

The United Nations hits the mark with their declaration that “Poetry reaffirms our common humanity by revealing to us that individuals, everywhere in the world, share the same questions and feelings. Poetry is the mainstay of oral tradition and, over centuries, can communicate the innermost values of diverse cultures.” Kipling is no exception to this: his sentiments about the value of traditional mills and milling, and his desire to see these traditional ways of life preserved are shared by many to this day. It is fortunate that even in this age where traditional mills are rare, they are in one way preserved for the future within the stanzas of poems such as Kipling’s.