“You worked blindly and towards an unknown end; but your end was certain.”

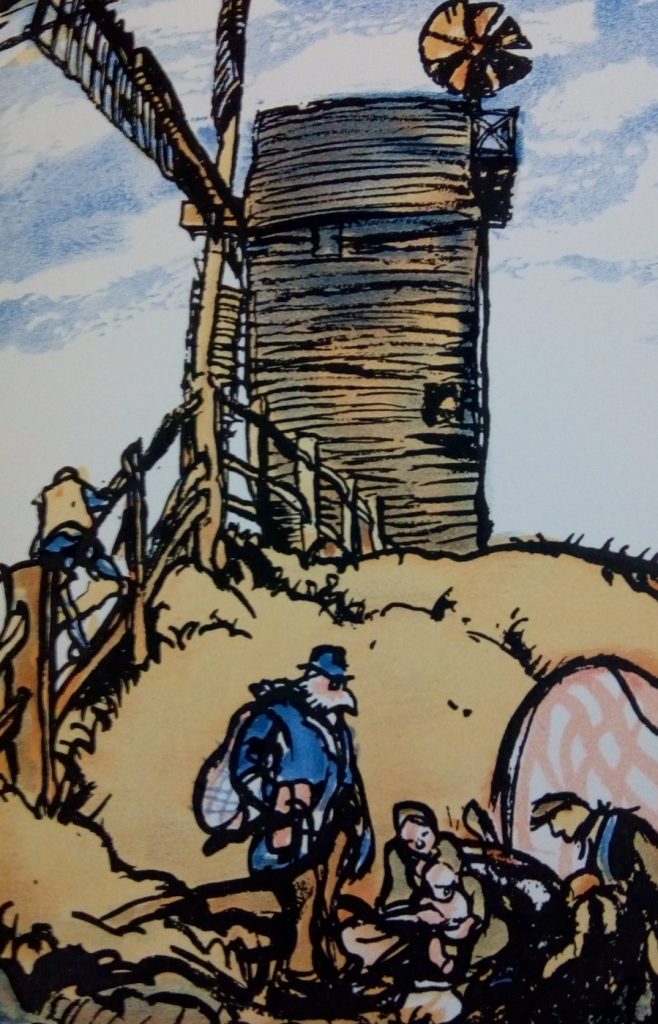

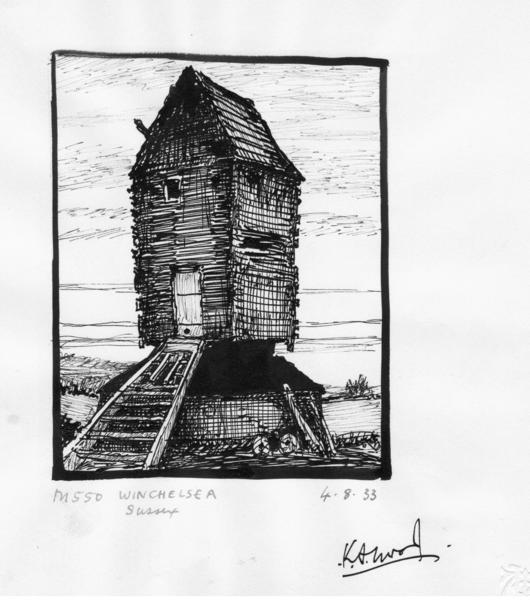

This beautiful watercolour is from a collection by Frank Brangwyn and Hayter Preston. The collection consists of a number of watercolours of different windmills, each with poetic anecdotes, which make up a beautiful and moving series exploring the state of milling and the decline of windmills. This watercolour is of St Leonard’s post mill in Winchelsea, East Sussex. Brangwyn describes it as:

‘built on frail, feminine lines. It reminded me of a respectable old woman whose dress has been patched and mended until very little of the original material is left.’

The poetic way in which Brangwyn talks about this derelict mill is an excellent example of the sense of attachment found across the collection:

‘O Mill, I thought, your fate is very like that of man. You worked blindly and towards an unknown end; but your end was certain. We also work on blindly, knowing next to nothing, guessing much, hoping that we may be respited even as the darkness closes round us…’

St Leonard’s Mill was a wind-powered corn mill built around 1760, and was in operation until the late 19th Century. It fell into disrepair and despite a number of restoration attempts, it ultimately collapsed during the storm of 1987 – leaving behind only a millstone, which was salvaged and used in the restoration of Lowfield Heath Windmill. According to Brangwyn, the mill has a somewhat macabre past:

‘As we walked over to the Mill, he told me an interminable story of a dead body being found near the place, and how a furious dispute between the coroners of Winchelsea and St. Leonards as to which of them should conduct the inquest, for half of the Mill is in one parish and half in the other’.

Whilst there is no other evidence of this specific story, it could well relate to an account given in the Sussex Agricultural Express on the 24th August 1861. According to this account the mill was undergoing repairs when, whilst hauling a new midding, the rope snapped – falling and killing the millwright. As there were no available witnesses from Winchelsea, jurors had to be summoned from Hastings and the inquest was held in the open air next to the mill.

Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) was an internationally renowned artist, the first to have a retrospective exhibition in the Royal Academy during his lifetime. Whilst he had no formal schooling in art, he did work for a short period of time under the famous textile designer, poet and social activist William Morris, which perhaps influenced both his passion for painting rural scenes. He is wonderfully poetic in the explanation of his love for windmills:

‘a spirit of something about Windmills, wholly indefinable. A sailing ship crossing the ocean is to some people as wonderful as a meteor crossing the heavens… and the majesty of Windmill sails revolving against the blue and green of quiet lands arouse in one sentiments as deep and mystical as one feels when gazing at the remote and whirling stars.’

As his wartime art would demonstrate, Brangwyn also had a passion for depicting simple labourers going about their work in his rural scenes. Whilst not an official war artist, he became heavily associated with war art as he completed many relevant commissions. Not all of them were appreciated, however – one particularly graphic painting depicting a British Tommy bayoneting a German soldier caused so much offence that it supposedly prompted the German Kaiser to put a price on his head!

This was not the only example of Brangwyn’s paintings causing controversy. In 1926, Brangwyn was commissioned to paint a pair of large murals as a war memorial to hang in the Royal Gallery of the House of Lords, commemorating the peers who were killed in the war. Upon completion the paintings were rejected, due to their overly grim, bloody and somewhat disturbing nature, and Brangwyn was instead commissioned to paint a further series of more lighthearted work. These 16 huge panels took five years for Brangwyn to paint, but when finished, the Lords decided that they did not ‘harmonise’ with the Royal Gallery as they were “too colourful and lively” – and they were also rejected.

These rejections hit Brangwyn hard and sent him into a deep depression from which he never truly recovered. However, despite this rejection that he so strongly felt, Brangwyn’s artworks continue to be celebrated to this day, particularly amongst mill enthusiasts. His beautiful and touching collection of windmill watercolours expresses a passion for the mills and the generations of millers that worked them and conveys a haunting sense of longing for a bygone way of life that many can associate with.

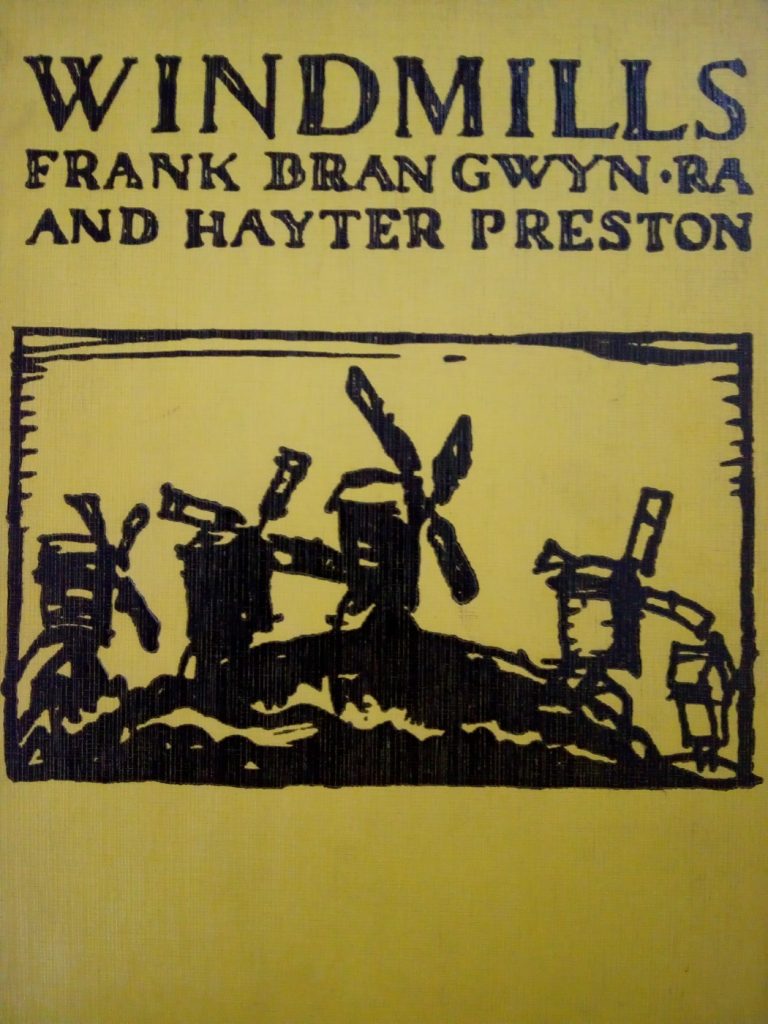

Gem from Brangwyn, F. and Preston, H. Windmills, John Lane, The Bodley Head, London (1923)

Related links

- Further Reading: Mills have inspired artists for hundreds of years. Whether in sketches, prints or watercolours you can learn all about the artistic soul of milling here.

- Water and Wind: You can read about another of these beautiful watercolours on our blog here.