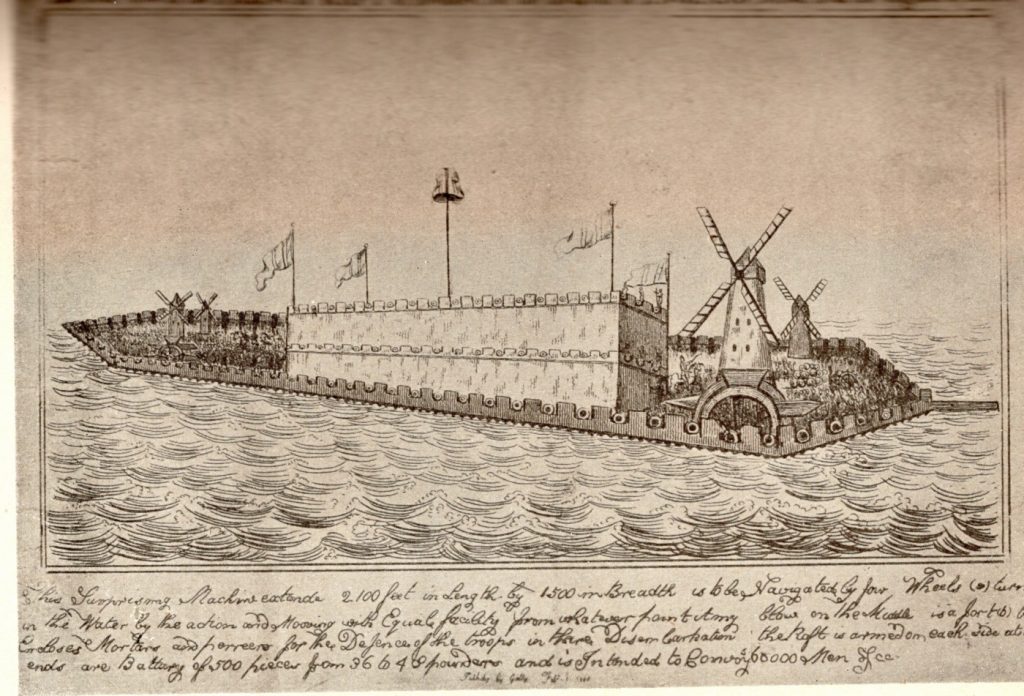

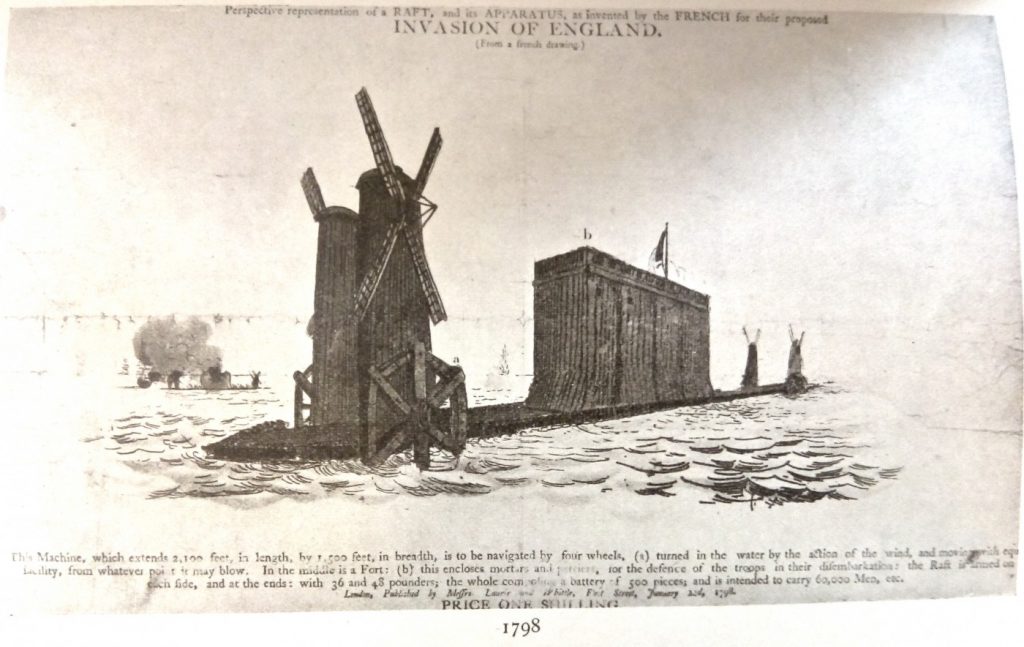

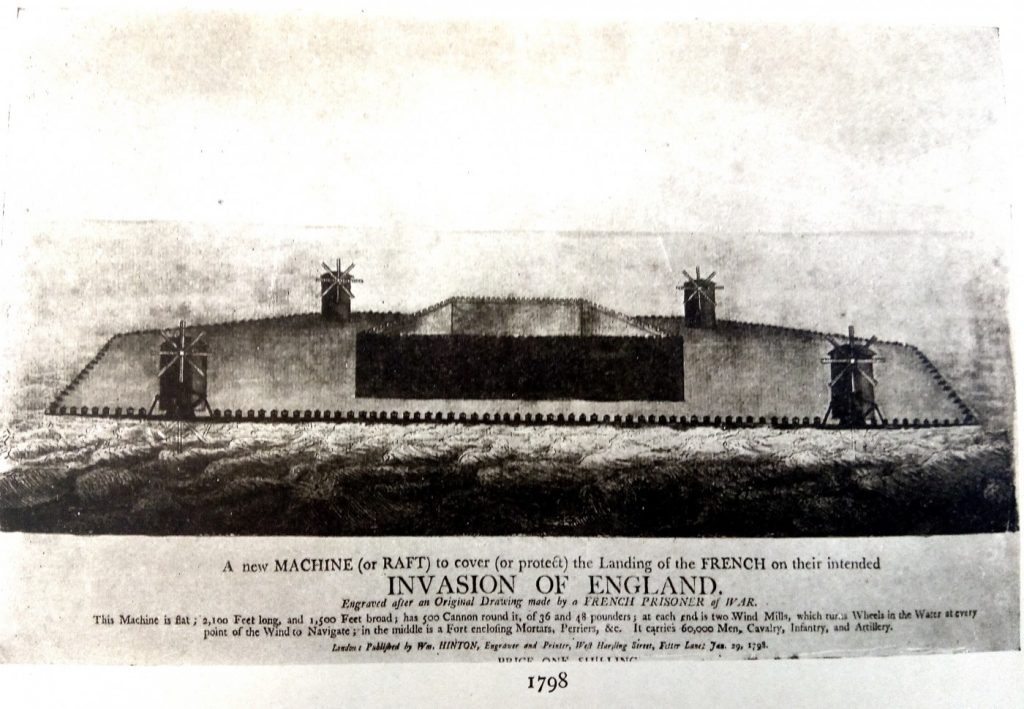

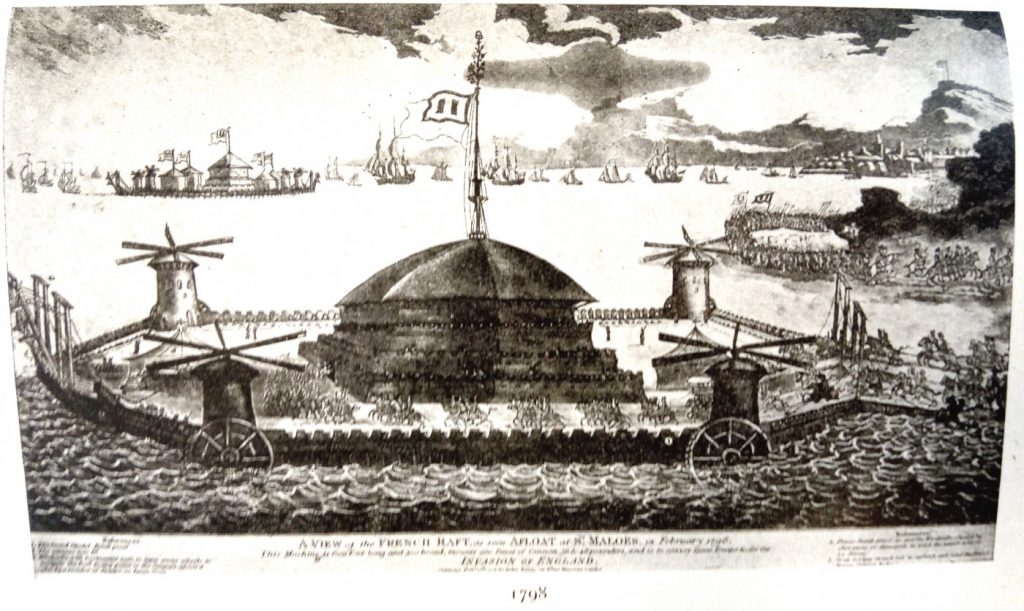

A supposed French invasion craft designed to cross the channel during the Napoleonic Wars.

_442_300_68.jpg)

In the late 1790s, Britain was gripped by the scare of an invasion by the infamous French warlord Napoleon Bonaparte. Over the channel he was amassing his forces; rumours of his conquests were rife and everyone knew he had set his sights on England as his next planned invasion. Indeed, a small French force even landed in Wales in 1797 (as part of a very brief and unsuccessful attempt at a diversion).

As it is wont to do (and was, even in the 18th century), the press took hold of the nation’s anxieties and began publishing satire about the supposed rafts full of military troops which would land on British soil. A variety of cartoons and reports were produced: the depicted rafts were all were impractically large and capable of carrying a very large number of soldiers, had some form of fortification in the middle and used wind-powered paddles as propulsion. These reports were all said to be supposedly from either ‘a prisoner of war’ or ‘a visitor recently from France’ to give them some form of credibility. The rafts quickly entered the public imagination and became a way of depicting the invasion threat in a comical manner, fuelled by Britain’s love of poking fun at the French (and perhaps also as a defiant stand against what must have been a very real and imposing threat). In the end, however, this invasion never came – Napoleon’s hopes dashed by Nelson at Trafalgar.

The Gem, an etching by Robert Dighton, was produced around 1798. Dighton was born in 1751 and entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1772, after which he set up as a drawing designer and miniature painter. He specialised in “dross”, caricatures of a more gentle nature than those by the likes of his main contemporaries, Gillray and Cruickshank. Dighton was a particularly colourful character: as well as working as a caricaturist and performing on the West End stage, in 1806 he was caught for stealing prints from the British Museum and selling them on. It was quite a scandal, but luckily for him he avoided prosecution by fully cooperating with the investigation. Robert Dighton died in 1814, leaving behind his children who also became caricaturists.

_300_208_68.jpg)

Remarkably, whilst these depictions of rafts are clearly absurd, there have been some attempts at creating boats powered by windmills. Some are less direct and have used them to produce electricity which is then used to drive the underwater propeller; but others have been directly linked through a drive shaft to the propeller. Indeed, with growing concerns over the environmental impact of international shipping and with new designs such as the use of windmills, large kites and solid sails, we may yet see a ship that resembles Napoleon’s folly.

Gem from Wheeler, HFB and Broadley, AM, Napoleon and the Invasion of England: The Story of the Great Terror, John Lane, The Bodley Head, London, Volumes 1 & 2 (1907)

Related links

- Further Reading: This cartoon is a piece of satire. You can learn more about this centuries old art form that stretches all the way back to the Ancient Greeks here.

- Anglo-French Trade during the Napoleonic War: The archive has a folder of research papers showing that despite the invasion fleet trade did continue to cross the English Channel.