Roller Milling Around the World: Australia

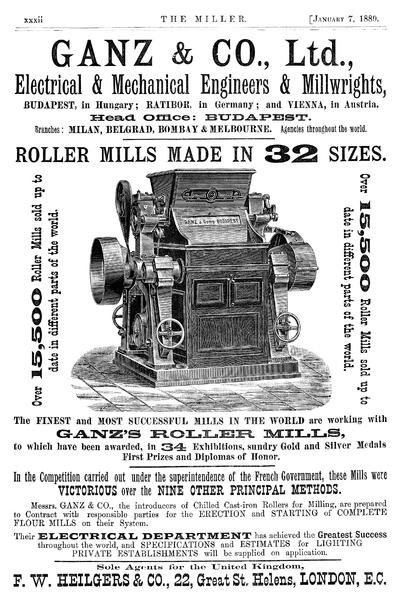

Australia was not at the forefront in the development of roller machinery but neither was it ‘far behind their American and European counterparts in moving toward the use of rollers’ (Jones, p.15). Indeed, the first complete roller plant was installed in 1881, not long after the first complete automatic roller systems had been installed in Europe. The man to order this plant was David Gibson of the Carlton Flour Mill, who is regarded as having the ‘honour of installing and operating the first true roller plant in Australia’ (Jones, p.16). The plant was installed by the Ganz Company and it was their chilled-iron rollers that would gain early prominence in Australia. However, other systems had already been trialled in other mills in Australia before this time. Messrs. W. Duffield and Company had twelve sets of Wegmann porcelain rollers in use in their Victoria Mill at Gawler by 1880.

The 1880s then saw the beginning of roller milling in Australia and it spread rapidly meaning that by 1888, country millers struggled to find ‘a market for all their flour manufactured by the old stone process’ so were ‘considering the advisability of adopting the roller system in their mills’ (‘New Roller-Mill Plant’).

However, some colonies, such as Western Australia, were slower to adopt to the new method of roller milling. The first machine was not installed in Western Australia until 1889 and the first complete plant, not till 1890. Indeed, by 1900, three of the fifteen mills in operation had still not changed over to roller machinery whilst by this time, some companies in other colonies were already expanding their mills given the success these new machines had bought them. The situation was therefore not the same throughout the country.

David Radcliffe tells us:

“There was also at least one local manufacturer of roller mills and ancillary milling equipment, Otto Schumacher of Port Melbourne. (He was the nephew of Ferdinand Schumacher, the ‘Oatmeal King’ of Akron whose company evolved into Quaker Oats.)

In 1885, Otto Schumacher started building entire flour mills based on imported roller mills (mainly Cornelius) in South Australia. Subsequently he designed and manufactured his own roller mills and was responsible for many of the early roller flour mills in West Australia. So he was in competition with local firms who installed Ganz technology as well as Thomas Robinson and Henry Simon. By the early 1920, Schumacher begun to diversify into the furnishing a much wider range of food processing facilities beyond just milling, although he still sold his roller mills up until the late 1930s.”

Engineers

As already stated, the Hungarian firm of Ganz and Co. were popular with Australian millers during the 1880s. Indeed, one author stated that ‘virtually all the…roller-mill plants in Australia in the 1880s’ were ‘Ganz equipped and designed’ (Jones, p.19). This Hungarian firm with its long and good reputation were up to the task of installing this machinery in the Australian mills. Indeed, Hungarians were very important to the milling industry in Australia as no Australians had experience with this machinery so companies would often look abroad to hire head millers with experience. W. S. Kimpton and Son was one such example as after having Ganz equipment installed during the 1880s, they then brought Steven Kovacs over from Hungary to be their Head Miller, a position he maintained till his death in 1898.

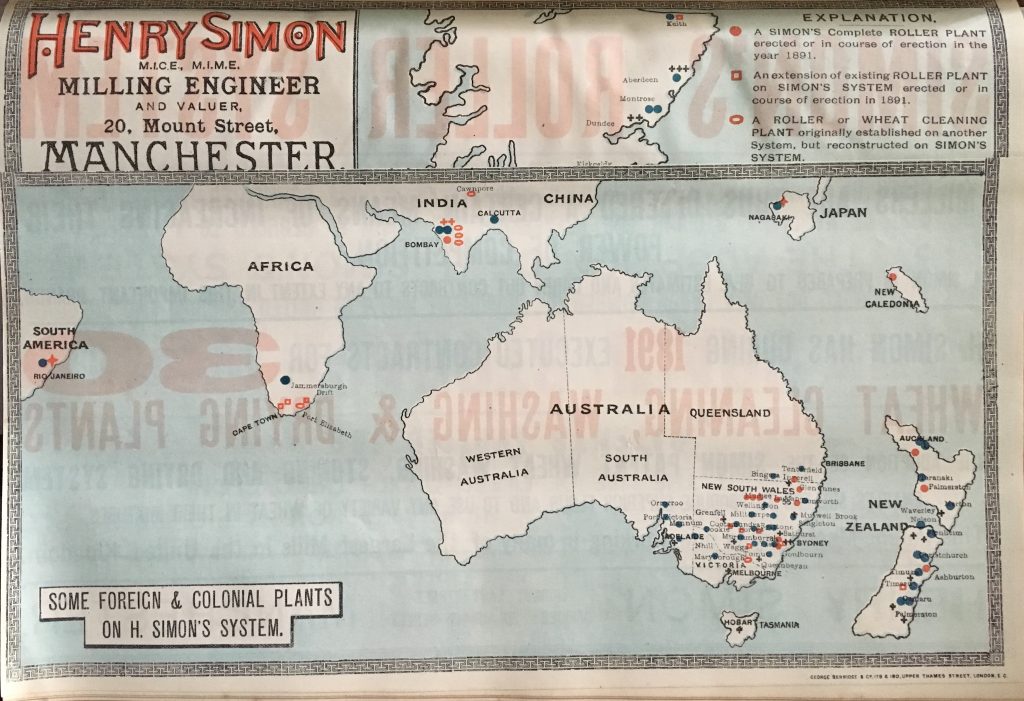

During the 1890s, the dominance of Ganz designs and rollers began to diminish as competition grew. Indeed, ‘Ganz, Simon, Turner, Robinson, Whitmore and Cornelius all fought for the Australian roller-mill business’ and it was eventually ‘the British firms, Thomas Robinson and Henry Simon’ who gained ‘the upper hand’ (Jones, p.24).

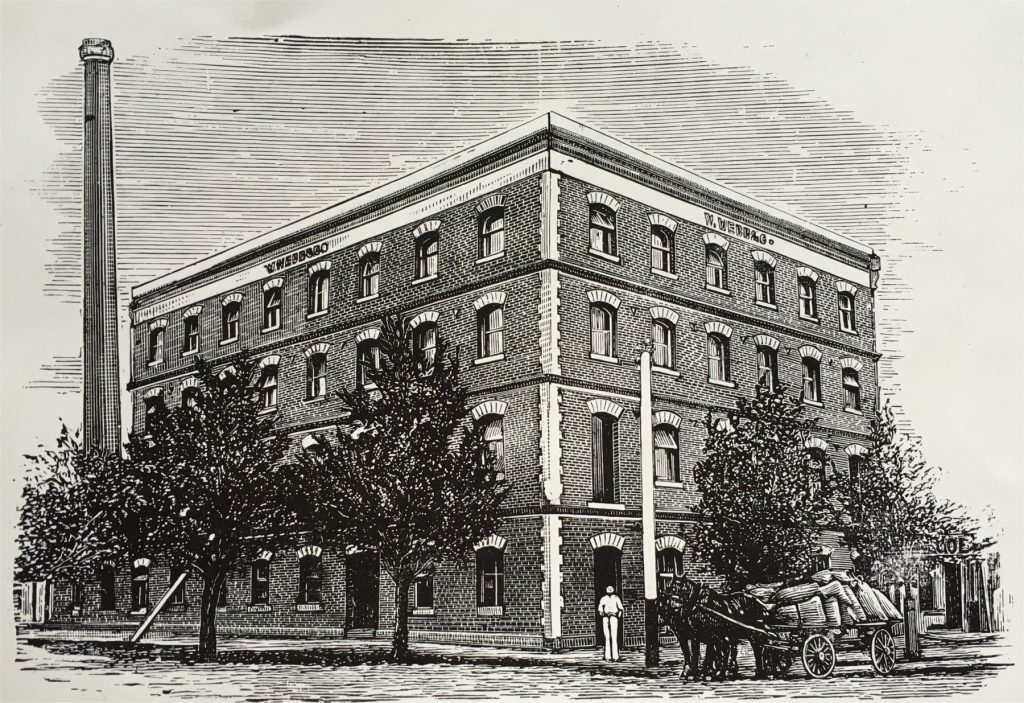

One such example of Thomas Robinson and Son Ltd. gaining the upper hand is Messrs W. Webb & Co.’s Roller Flour Mills, Sandhurst, Victoria, which had a 12 bags per hour system installed by Robinson in 1888. They stated that they wished their machinery to have ‘all the latest improvements which had yet been introduced’ (‘W. Webb and Co.’s Flour Mills’). Their system produced two grades of flour, called Golden Eagle and Silver Eagle, which was described as ‘the finest flour that is possible to be manufactured’ (‘W. Webb and Co.’s Flour Mills’). Their head miller was Mr. J. Wigful, not from Hungary but from Sheffield, U.K., where he had ‘gained a thoroughly practical knowledge of Robinson and Co.’s system in his uncle’s extensive mills’ (‘W. Webb and Co.’s Flour Mills’). So Robinson’s machinery was growing in popularity in Australia and examples like Messrs W. Webb & Co.’s mill with the description of it being ‘a splendid flour mill and containing machinery which cannot be surpassed for excellence’ would only help this popularity increase (‘W. Webb and Co.’s Flour Mills’).

Robinson’s biggest competition would come from Henry Simon Ltd. Henry Simon had built offices and workshops in Sydney during the 1880s due to the custom he was already receiving and in hope of more. Messrs. Fielder and Sons of Phoenix Mills from Tamworth, New South Wales, were one of the first to install Simon machinery in New South Wales in 1890. However, this was not the end of their association with that company as twelve years later, they returned to Simon to upgrade to a ten-sack plant.

Similarly, W.S Kimpton and Son also repeatedly turned to Simon engineering, after using many other types of machines. In their mill at Goulburn in 1904, they had ‘four sets of rollers by Ganz, four sets of double stands by T. Robinson & Sons, and four sets of stand by Oexle et Cie, Budapesth’. The only Simon machinery to be found there was one scourer (‘Another Mill at Goulburn’). However, when in the same year their Kensington Mill burnt down, it was to Simon Ltd. they turned to install the machinery in their re-built mill. In 1907 it was upgraded by the same company so that by 1908, they claimed to have ‘one of the best and most up-to-date plants in Australia’ (Jones, p.37). Their mill manger helped to accomplish this success. He was a young but experienced Australian by the name of George B. Harris. He had worked for Gillespie Brothers and Company, during the 1890s, for nine years until he went to England in 1902 where he worked with Henry Simon Ltd. He then returned to Australia in 1904 to install Simon machinery and act as head miller and manager, first for Mungo, Scott and Co., and then for W. S. Kimpton and Son.

So by the eve of the First World War, the milling industry in Australia was looking healthy. Although sluggish at the start, most millers had converted to the roller system and were producing better flour which was received gratefully at home and, more importantly, abroad as their exporting business grew.

World War I

As part of the British Empire, Australia was involved in the war from the beginning. Life would change for those in country, men would leave never to return; the Prime Minister would be expelled from his own party; and the flour industry would come under governmental control. However, this control was not necessarily detrimental to the industry. There was a high demand for exports of flour, especially from the ‘beleaguered British Isles’ which ‘virtually ensured three-shift running for most Victorian mills’ (Jones, p.45). This demand meant that the state of Victoria alone exported 135,180 tons of flour in 1917-1918.

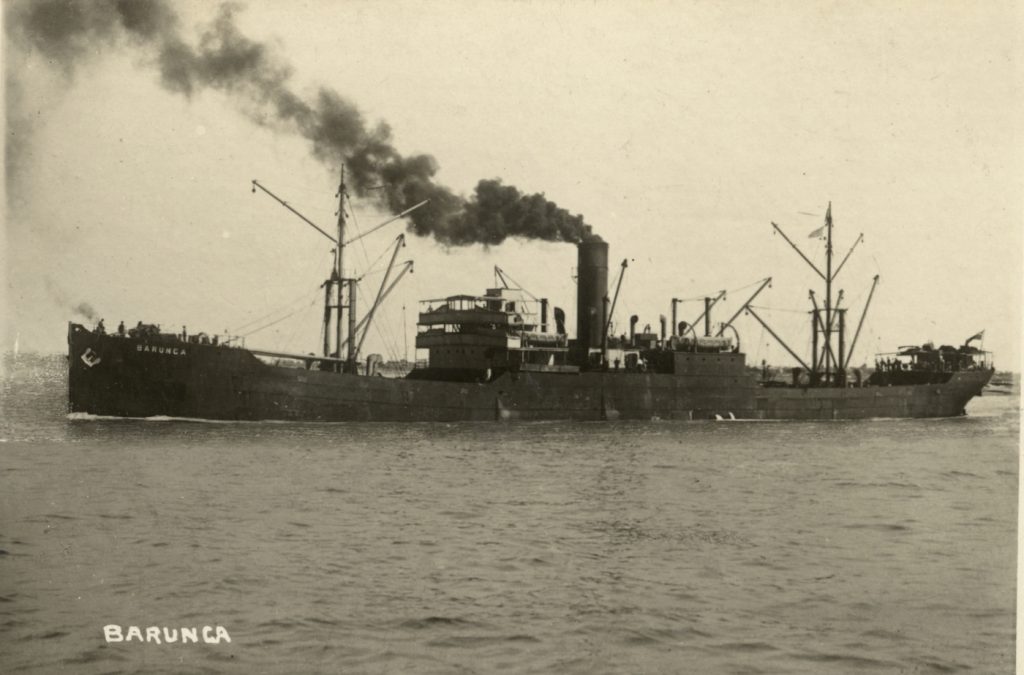

However, this export business was by no means assured. Facing an increasing fraught situation at home, British shipping was withdrawn from Australia. The Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, then formed the Commonwealth Line in 1916 to continue being able to export goods. This Line was formed out of 15 tramp-steamers, purchased in ‘secret’ to ensure they would not be requisitioned, along with 26 captured German ships, including the ‘Barunga’ as seen below. This Line ensured that the Australian flour export trade continued and that Imperial Flour Orders could be met.

The post-war situation in Australia was less positive. War-time controls continued and the export trade practically ended as

‘The Australian Wheat Board persisted in its policy of refusing to reduce the price of wheat to be gristed into flour for export, to a figure which would enable Australian millers to compete against other countries’ (Australasian Baker and Millers Journal XXV)

The situation grew so serious that some mills were prepared to close for a time to allow their accumulated stocks to be sold before re-opening. Eventually, under immense pressure, the Australian Wheat Board lowered the price for wheat exported as flour and itself ceased operations in 1921. This allowed companies to again export flour and try to regain the custom they had lost to American and Canadian millers. However, this was not the last time the Australian Wheat Board would be in existence…

World War II

The outbreak of hostilities in 1939 would again bring Australia into another World War, however, this time they would have the closer enemy of Japan to deal with as well.

The Australian Wheat Board was re-formed and it controlled the allocation of flour exports along with wheat disposal. Initially, the impact of the war was small, as can be seen through the example of W. S. Kimpton & Sons mills in Victoria. In 1940 they exported 63,534 tons of flours out of the total 93,455 tons produced. Indeed, throughout Australia, millers exported 100,000 tons of flour to Japan alone in that year. However, after this exports throughout the country and in the example, dropped. 1942 saw 20,653 tons exported by Kimpton and Sons and only 12,440 tons in 1943 (Jones, p.63). This drop came about as the markets in East Asia had been lost due to Japanese occupation. Shipments to allied countries should have seen a rise take place in 1944 but there had been a drought from 1943-1945 meaning there was little grain available to be milled. Kimptons’ reached a low of 3,733 tons exported in 1945. Thus the Second World War had a greater negative impact on the Australian milling trade than the First had.

Post-War to Today

Immediately post-war, however, Australian millers found themselves in great demand as there was a need for flour world-wide. The Kimptons exported on average 30,000 tons each year as they recovered from the war years. Even in the early 1950s this demand was still present, indeed, the ‘Overseas demand appeared to be insatiable’ (Jones, 116). In Victoria, the 14 metropolitan mills and 25 country mills were virtually running to capacity to fill the export orders. However, this demand did not last and its withdrawal caused the end for many Australian mills.

The export trade began to diminish during the 1960s and 70s as foreign mills had recovered, so no longer needed to rely on exports, and less flour was being consumed generally, both at home and abroad. Those still milling in Australia in the 1970s were producing less flour but many others had stopped milling altogether. A ‘rehabilitation scheme’ was run by the Flour Millers’ Council and was funded by large companies. This scheme allowed the Council to purchase mills for ‘a price based on a formula embracing rated capacity and level of local sales’ (Jones, p.117). After this purchase, the machinery was usually destroyed but it ensured that the miller did not go bankrupt.

The rate of the closure of mills can be seen by looking at the figures for Victoria. In 1950, there were 39 mills in the state; by 1970 there were 16 and by 1980, 5 mills. The majority of these mills were purchased as part of the ‘rehabilitation’ programme as the milling industry was consolidated into a few large Tcompanies that were able to weather the storms and survive. Today, these companies include Allied Pinnacle (formed when Allied Mills and Pinnacle Bakery merged in 2017), the family owned Laucke Flour Mills, and Weston Milling (part of MAURI anz).

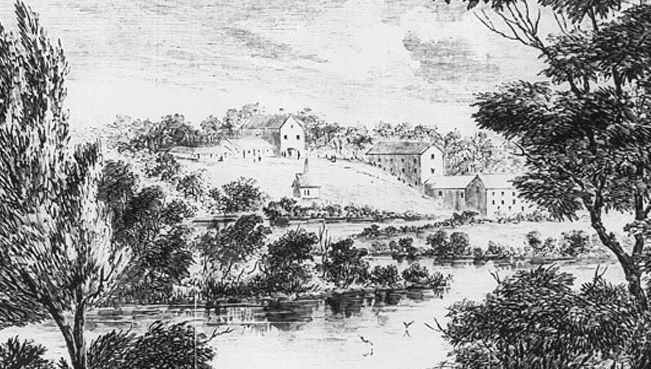

Despite the dramatic reduction in the number of flour mills in Victoria, their history was not lost. The history of the region, and the industry, has survived in mills like Anderson’s Mill, Smeaton. Although no longer working, the building itself has been preserved as an example of the industry and the area. Built in 1861 during the goldrush era ‘in response to local needs’, it ran for just under 100 years, closing down in 1957 (Anderson’s Mill, p.1). It was abandoned until the 1970s when it was included on the Historic Buildings Register. By the end of the 1980s it had been purchased by the State Government and the conservation of the building truly began. Today, located in Smeaton Historic Area, it hosts an annual festival held by the Newlyn Netball and Football Club celebrating food, wine and music.

Victoria is not the only state where mills have been preserved. Tremains Mills in Bathurst, New South Wales is another example of a mill building being restored. Built in 1857, this mill only closed down c.1980. Today, the mill and its silos are heritage listed and are currently being restored. Its machinery has also been preserved, including a Robinson & Son Ltd. roller mill and another roller mill recently donated by Laucke Flour Mills. This preservation work means a vital part of the history of the flour milling industry is not forgotten and is retained for future generations.

Tasmania’s first roller mill

The Ritchie milling dynasty began with Thomas Ritchie, who by 1834 had built a flourmill at Scone, near Perth. Sons Thomas, John and George were involved with milling in Longford, but it was David who turned Scone Mill into one of the leading mills in Tasmania, producing high standard flour as well as most of Tasmania’s oatmeal. Following the 1870 loss of the mill to fire, he moved into Launceston, buying the Cataract Mill in 1876. Ritchie was the first Tasmanian miller, in April 1889, to convert from stones to a complete roller mill, and in 1910 D Ritchie & Son built Tasmania’s first concrete grain silos. The comparatively small mill continued operating until bought by Monds & Affleck in 1973 and closed.

Sources:

*Image of Barunga ship courtesy of State Library New South Wales, FL1149419*

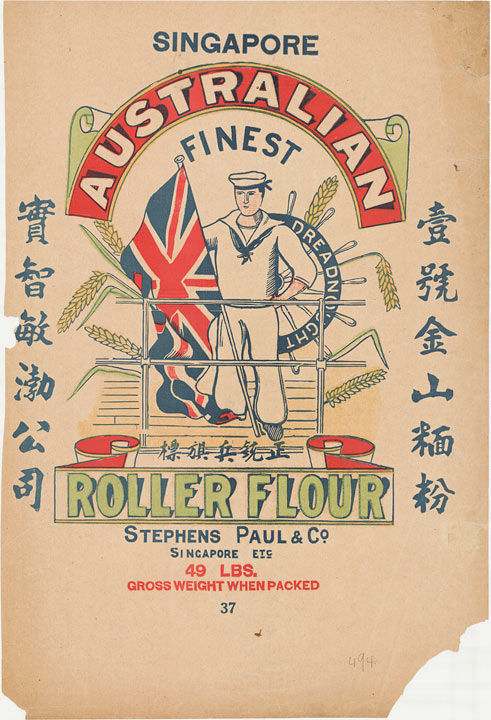

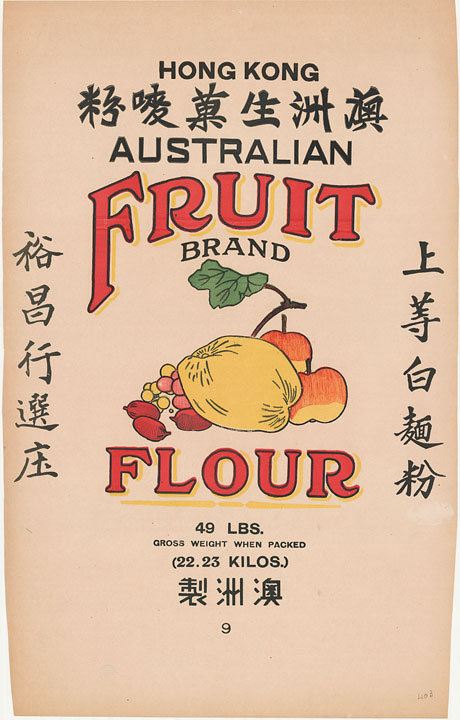

*Images of ‘Finest Australian Roller Flour’; ‘Australian Finest Roller Flour’ and ‘Australian Fruit Brand Flour’ courtesy of State Library New South Wales, XX/125*

*Image of Laucke Mills by denisbin (CC-BY-ND 2.0)*

‘Another Mill at Goulburn’, The Millers’ Journal, February 24, 1904, p.73.

‘New Roller-Mill Plant’, The Adelaide Observer, Saturday December 3, 1888, p.1037.

‘W. Webb and Co.’s Flour Mills’, The Bendigo Advertiser, Saturday, June 23, 1888, p.3.

Australasian Baker and Millers Journal XXV, March 31, 1921, pp.76-78.

Cookson, Mildred, ‘Milling around the World at the Mills Archive – British Empire Mills’, Milling and Grain (February, 2016), pp.10-11.

Department of Conservation and Environment, Anderson’s Mill, Smeaton, (Victoria, 1990).

Jones, W. Lewis, Where Have All the flour Mills Gone? A History of W.S. Kimpton and Sons – Flour Millers 1875-1980 (Melbourne, 1984).

Lang, Ernie, Grist to the Mill: A History of Flour Milling in Western Australia (Perth, 1994).

Tasmanian roller mill http://www.slv.vic.gov.au/pictoria/gid/slv-pic-aab34440 Modern Photograph 2018 courtesy John McCorquodale