Building a Mill: Choosing the Machinery

So now you have a mill building fit for purpose but it is empty and needs to be filled with the best modern machinery possible. The main two decisions that have to be made are: what machinery do you want installed in your mill and who should install it? One could either install the full roller mill system or just roller machinery. This section will focus upon how the decision is made rather than the decision itself.

To make this decision, a miller could take advantage of several different methods available to him:

Exhibitions

Before choosing to commit to a particular piece of machinery or engineering company, it is best to have seen the machinery in action first. A way of achieving this was to attend an exhibition, something many British millers did and it is arguably thanks to exhibitions that roller milling ever succeeded in Britain. The most common type of exhibition in Britain was those put on by the Royal Agricultural Society of England (RASE). They held shows annually with some examples being: Taunton in 1875, Birmingham in 1876, Liverpool in 1877, Bristol in 1878, Kilburn in 1879, and Carlisle in 1880. The exhibition in Kilburn is remembered as notable with 12 exhibitors of chilled iron rollers including Simon with Daverio’s design, Carter, Buchholz with Ganz designs and Throop as an agent for Gray.

(Simon and Robinson advertisements for Royal Agricultural Shows in Kilburn, 1879 and Maidstone, 1899)

Britain and the RASE were not the only ones to hold exhibitions as there were numerous other international milling exhibitions too. In 1878 there was an international exhibition in Paris and in 1880 there was one in Cincinnati, USA. W. D. Gray, the man who designed and invented Gray’s patent noiseless roller, attended this exhibition and described it at a later date:

‘our rolls were exhibited, I think, for the first time in public. We had them running, and they attracted a good deal of attention’.

‘The English millers at this time were getting quite anxious as to the conditions of their mills, and they were looking for improvements. There was quite a delegation of them at this convention. So it proved to be quite an important event, both for English and American millers.’ (Gray, ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling’, Part X).

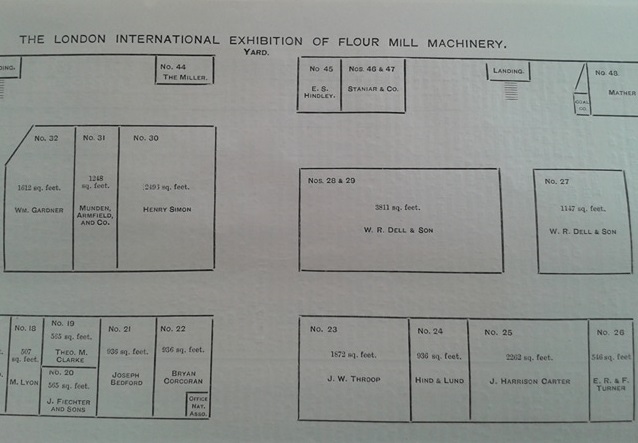

Whilst Gray may claim that this exhibition was important for both English and American millers, it was not the most important for the English. In fact, Voller believed that historically, ‘a position of singular interest will certainly be assigned to the year 1881, the point at which accelerated reform actually commenced’ (Voller, p.28). As the Cincinnati exhibition had been in 1880, it could not have been the point referred to, instead that was the international exhibition held in Islington, London in 1881. As good as the previous RASE exhibitions had been, Glyn Jones described that‘milling machinery had not been specially classified or concentrated’ at their exhibitions (Jones, p.146). What was needed was an exhibition in a covered site where realistic demonstrations could be given. This is what was planned for 1881, and the International Exhibition of Flour Mill Machinery was held in the Agricultural Hall, Islington, London. The exhibition was a great success with around 60 exhibitors, many displaying roller mills including Dell, Carter, Simon, and Throop, with nearly 21,000 visitors.

The success of the exhibition was mainly judged by number of orders companies received for their products and these numbers dramatically increased in the years following the exhibition. Mr. W. Hooker of Chartham Mill, Canterbury, was an example of this: ‘He attended the Bakers’ Exhibition in London where a roller mill was in operation. He was impressed with its performance producing white flour which was then in demand. He offered to purchase the plant if the milling engineer would install it in the Chartham Mill. This they agreed to do’ (Hancock, p.6). This event took place at an exhibition itself but it also had had a longer impact in the following months. Indeed, the 1881 exhibition stood out so much that Henry Simon was still highlighting it over ten years later: ‘the great exhibition at Islington in 1881, which must still linger in the recollection of many millers as an eventful epoch, a veritable landmark in their career’ (Simon, 1892, p.2).

However, others were less enthused by the exhibition and in editions of The Miller following the event many wrote in stating their unhappiness. One letter from ‘”French Burr” claimed that he knew of instances where ‘trade has been lost because the flour has not been so good after the introduction of roller mills’ and suggested that the best flour could only be made ‘from the old style machinery’. Another letter, this one by “Quern”, expressed concerns over how roller milling could be made to pay as ‘Millers do not find it easy to make the manufacture of flour pay now’. These were concerns shared by other millers but the majority clearly did not agree with them and Theodore Voss was correct in his letter, countering “French Burr” and “Quern”, to state that ‘roller mills will supersede millstones slowly but surely’.

The adoption of roller machinery did not see the end of exhibitions either. They are still running today on a global scale. Within the Milling and Grain monthly magazine, they list events, including exhibitions. In the September 2017 edition they listed 20 events taking place internationally concerned in some way with milling and/or grain from September to the beginning of November. These events are held throughout the world in Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, Australasia, and Africa. The need to feed the world keeps pushing the milling industry forward and milling exhibitions and conferences allow ideas to be shared and the best designs to be utilised. That is why milling exhibitions are as important today as they were in the nineteenth century at the beginning of the roller mill revolution.

Visiting other Mills

Along with exhibitions, another way of seeing the machinery at work was to visit a mill. Millers are often very secretive and many would not allow others to view their mills. Indeed, when W. D. Gray was in Europe and visiting Ganz and Co. mills, he was not allowed into one as ‘The manager did not allow Americans to go through his mills’. Gray generally criticised European mills for their secrecy and stated that it had prevented the quick growth of roller milling by keeping their doors shut and methods hidden. In contrast to this, he described that ‘The American miller has been more liberal in throwing his mill open to strangers and visitors than the millers of any other country’, thereby advancing the growth of the industry’ (Gray, ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling’, Part IX).

However, after the Islington exhibition those few mills that did have rollers installed were more open to showing their mills. Henry Simon and Carter both advertised that could arrange visits to mills using their machinery. Many took them up on these offers and visits were organised by others too. For example, during conventions in Glasgow, Dublin, and London in 1885, 1886 and 1887 respectively, nabim made arrangements for mills to be visited. In the 1885 trip to Glasgow, 11 mills were opened and over 70 visitors went to Craighall Mills to see the Simon System. There was clearly a great desire to see these machines in action and not just hear or read about them. Once something has been seen and the evidence of it made real before your eyes, then it had to be believed.

Catalogues

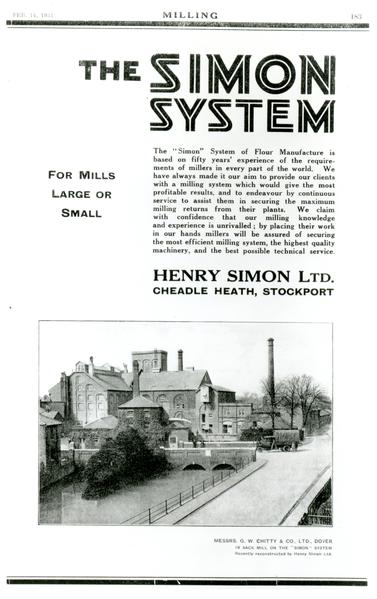

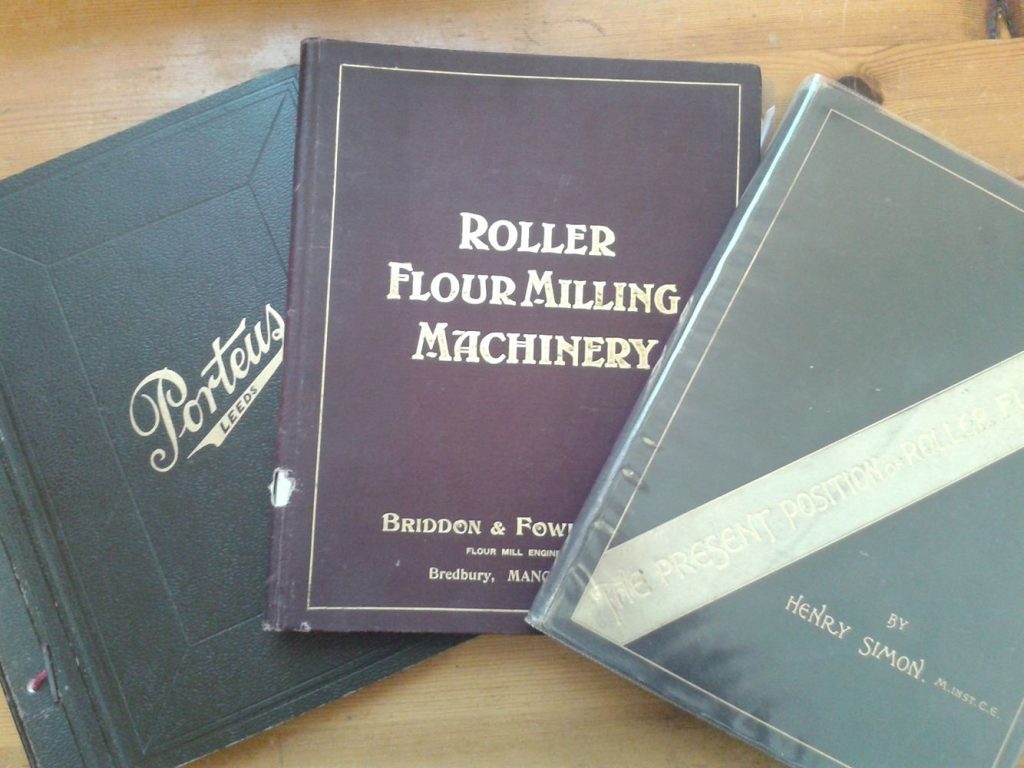

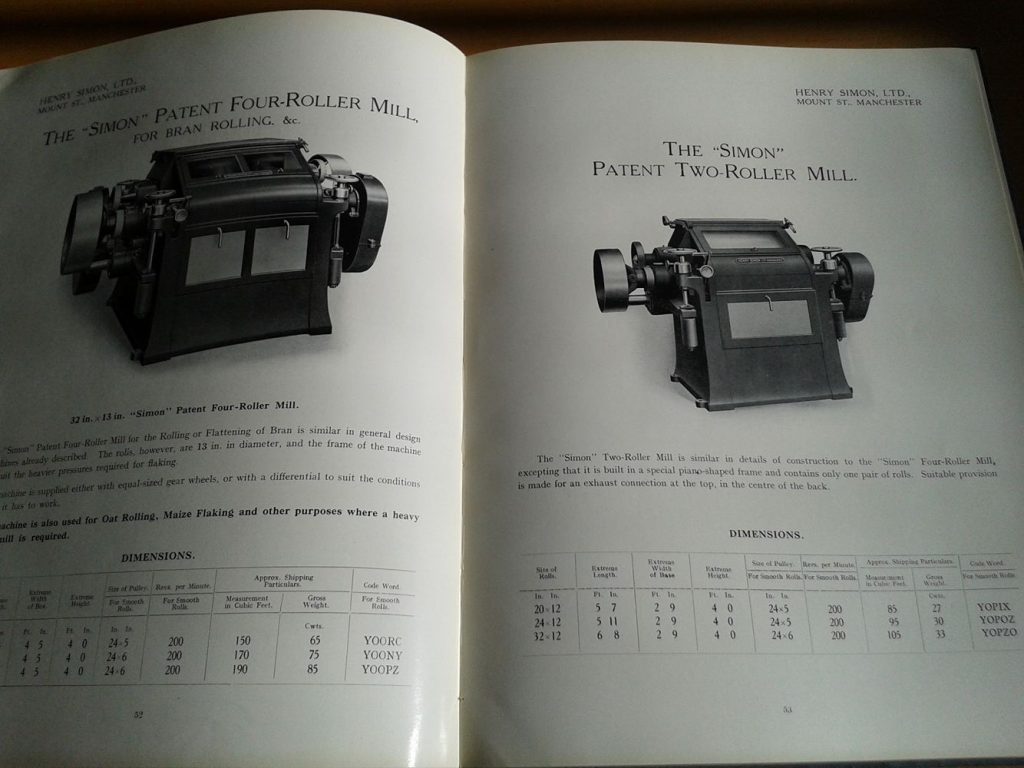

However, this did not mean that written material did not have its place. Journals would contain advertisements of different companies and their machines, as well as including articles on different machinery. Furthermore, the companies themselves produced catalogues containing information on all the different machines they made. This would include an image of the machine followed by a description of the machine with details (sometimes including the price). They would give a prospective buyer all the details they would need to make a decision about a piece of machinery, especially if it was just a new version or a replacement.

Moreover, advertisements often worked in conjunction with exhibitions. Henry Simon’s adverts frequently stated where their machinery could be found and if he would be attending an upcoming exhibition. It meant that people could be prepared when attending an exhibition and know what they could find there. Indeed, they may purposefully go to the exhibition just to see one specific demonstration. Advertisements and exhibitions were therefore complementary to each other.

So, a prospective miller would do best to attend exhibitions, or visit a mill, to see the machinery that they are contemplating buying in action. Further research and reading of journals, magazines and catalogues would add to the knowledge and put them in a better position to judge what they see. You can then decide on the best machinery to be installed and who you wish to install it. As can be seen in the construction page, this decision was often best made before building a new mill as ample space could then be provided for the machinery. Nevertheless, when this stage has been reached, the mill built and fitted with machinery, it is then necessary to consider who will be working the machinery…

Sources:

‘The Late Milling Exhibition’, The Miller (4 July, 1881), p.370.

Gray, W.D., ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling, Part IX’, The Northwestern Miller (20 December, 1899), pp.1198-1199.

Gray, W.D., ‘A Quarter-Century of Milling, Part X’, The Northwestern Miller (27 December, 1899), pp.1215 & 1243-4.

Hancock, Philip, ‘Extracts from “Rambling Recollections of a Rural Miller”’ (1980): FULL-22162.

Simon, Henry, The Present Position of Roller Flour Milling (Manchester, 1892).

Voller, William, ‘Five decades of flour milling’, Milling (September, 1921), p.28.