| It’s time for the third in our series of 21 gems of the Mills Archive. In the last two newsletters we looked at both the oldest and the largest artefacts we hold. This week we are looking at the oldest document in our archives, a legal deed in the Mildred Cookson collection dating from 1552. |

The deed

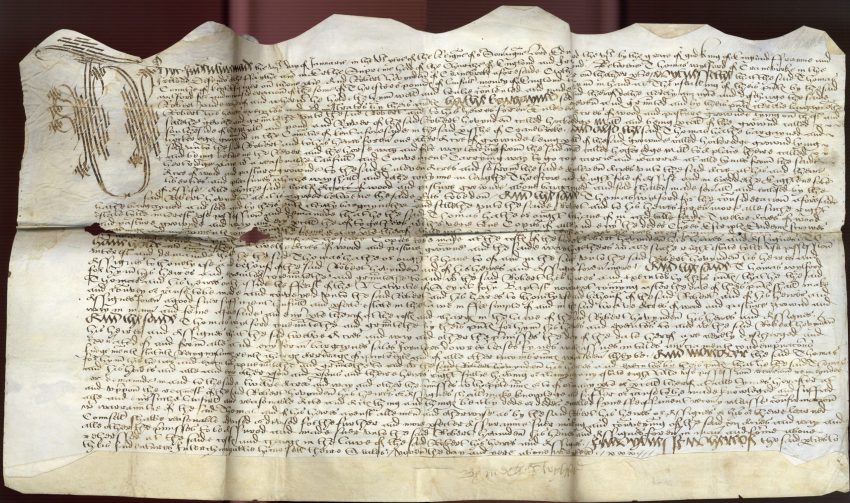

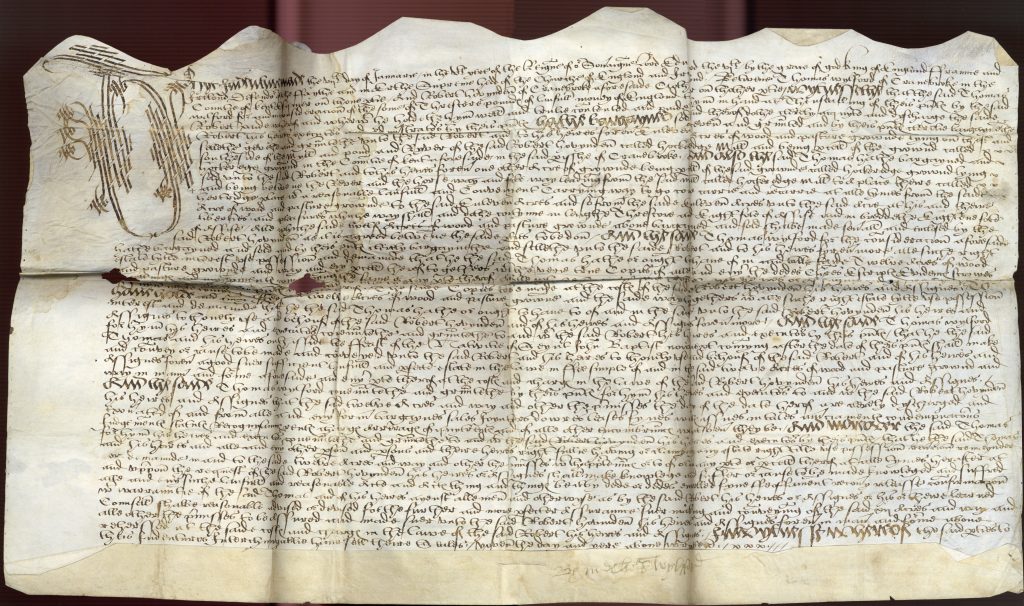

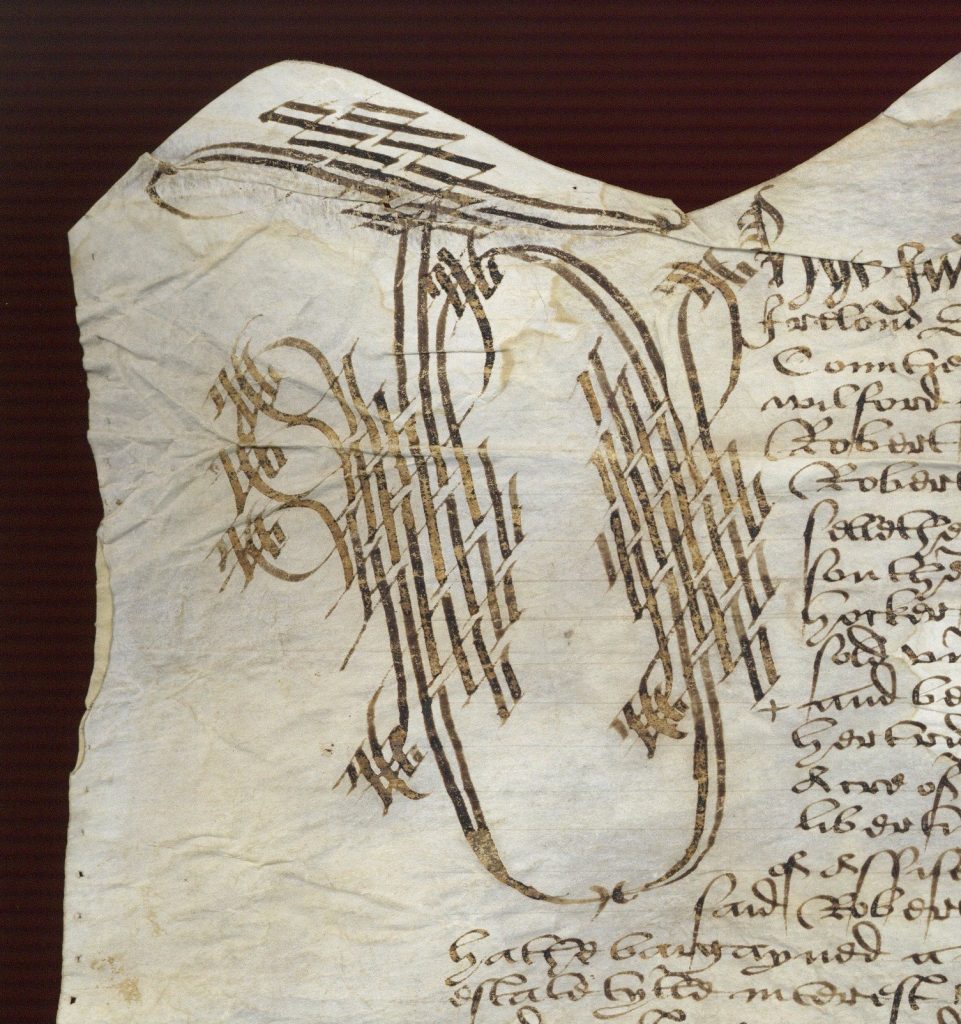

| It is an ancient looking, wrinkled piece of velum (animal skin), around 56 by 33 cm in size, marked with creases from centuries of being stored folded, torn in places and covered with an archaic script which few people today can decipher. An elaborate swirl of ink full of zig-zaggy lines in the top left corner might look like a piece of meaningless decoration, but it is in fact the letter ‘T’, beginning the word ‘Thys’. |

| The opening of the document reads: Thys Indenture made the vijth day of Januarie / in the vth yere of the Reigne of our Soveraigne Lord Edward the vjth / by the grace of god King of Englond Frannce and Irelond Defendour of the Faythe and in Erthe Supreme Hedd of the Churche of Englond and Irelond… ‘Indenture’ is a term used to describe a variety of different types of legal deed. The name comes from the French endenter, from dent ‘tooth’, and describes the teeth-like indentations at the top of the document. Originally, these resulted from the fact that two copies of the text would be written at opposite ends of a large vellum sheet. It would then be cut in two with one copy given to each party to the deed. The authenticity of each copy could then be demonstrated by matching up the two halves again. |

The contents of the deed

| Old deeds can give the impression of a wall of text, written in the form of an endless sentence without punctuation, making it very hard to interpret, even if you able to figure out the script. They tend however to follow a very standard structure. Standard phrases written in a larger script indicate where a new section begins. |

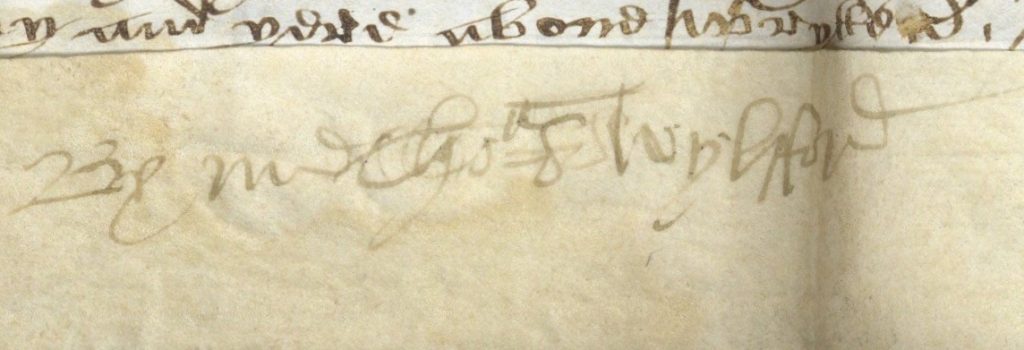

| In this case, after the opening sentence given above, indicating the date as the 7th of January in the fifth year of the reign of Edward VI (1552), the deed goes on to introduce the parties, namely:Thomas Wylford of Cranebroke [Cranbrook] in the Countie of Kent Esquier Robert Hovynden of Cranebroke Clothier The word ‘wytnessethe’ then introduces the details about the agreement – in this case that Thomas Wylford (also spelt Wilford), ‘for and in consideracion of the some of Threscore poundes’ is selling to Robert ‘Enleven [eleven] Acres of wood and pasture grownde’. The land was known as Hockeredge Ground and was on the south side of Hockeredge Mill, already owned by Robert Hovynden. Thomas is also selling another acre ‘lying and being betwene the Rever and the horse way and fote way leading from the said mill’, along with a ‘carrying way’ connecting the two areas of land. The deed then makes various other provisions, such as that Thomas will provide Robert with ‘verie true Copies of alle and every the dedes Charteres Escriptes Evidences scrowes wryttinges and mynymentes’ that may be relevant – in other words, any other legal documents already in existence relating to this land. He likewise affirms that the land is ‘clerely dyscharged and exonerated of and from alle and every former bargaynes sales Joynters dowres leases fynes willes assues intales amerciamentes condempnacons Judgementes statutes Recognysaunces rentes charges Arrerages of quytrentes and of alle other encombraunces whatsoever they be.’ Finally the document is signed at the bottom ‘by me Thos Wylfford’. |

| You can find out more about the structure and use of historic deeds in this online resource provided by the University of Nottingham: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/deeds/skills.aspx |

The script

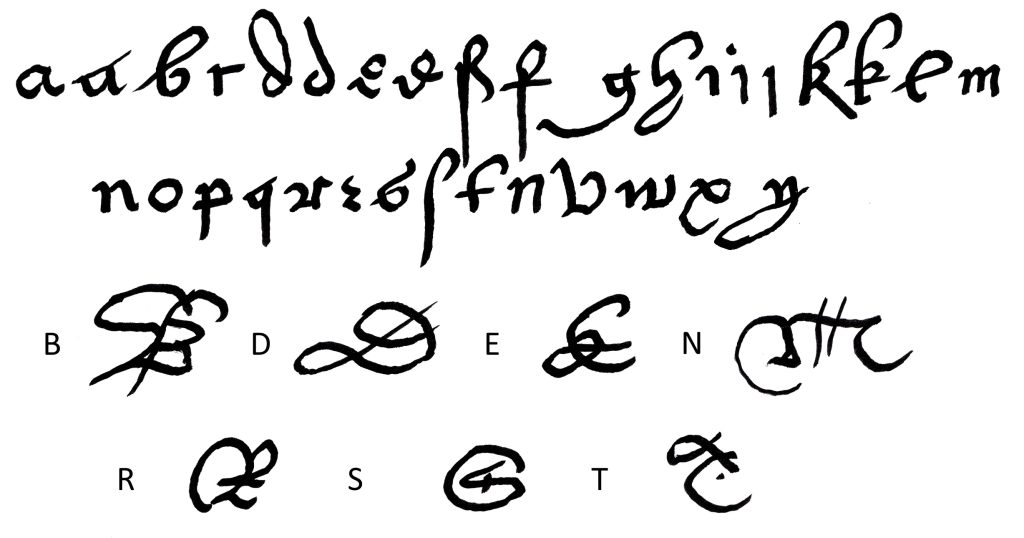

| Although the script of the deed might seem indecipherable, once you have become familiar with the letter shapes it is not too hard to read. The script is known as Secretary Hand, a style of cursive writing developed in the 16th century, designed to be written with speed and employing many loops and curls, with letter shapes that would now seem very unusual. The script continued in use until the Copperplate script became predominant in the 18th century, although some nineteenth century legal deeds in our collections are still written in a calligraphic variant of Secretary Hand. There were many variations of Secretary Hand. The lowercase letterforms found in this document are reproduced below, with some examples of capitals. |

Hockeredge Mill

| Hockeredge or Hockridge Mill still exists today, although it has now been converted to dwellings known as Hocker Edge. |

geograph.org.uk/p/4338619

| Other deeds and records relating to Hockeredge Mill can be found at the Kent County Archives. The earliest, from 1523, records the sale of the mill by James and Thomas Wylford to Alexander Courthope. Courthope left the mill in his will to his son William, who sold it to Robert Hovynden in 1551. The Hovyndens continued to own the mill for over 150 years. It later passed to the Bonnick family. The mill was the last watermill in the parish to work, ceasing in around 1899 and remaining derelict for many years. At the time it ceased working it had an 18 foot wooden waterwheel manufactured by Warren of Hawkhurst, a 16 foot diameter pitwheel and four pairs of millstones. It was converted into a house in the mid 20th century. |