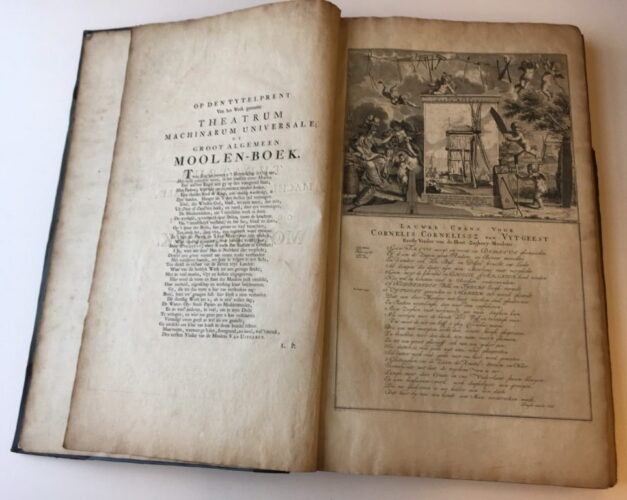

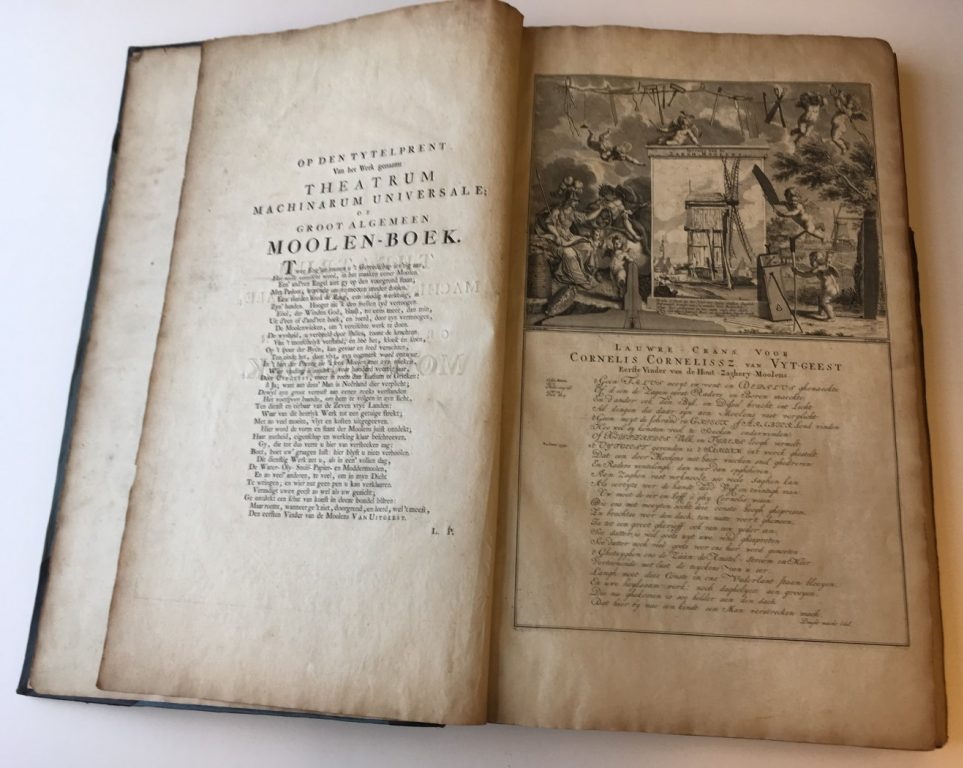

| In our special collections here at the Mills Archive, we have an original copy of the Theatrum Machinarum Universale of Groot Algemeen Moolen-Boek, which translates as the Universal Theatre of Machines or Large General Mills Book, produced by Johannis van Zyl and Jan Schenk in 1734, and republished in 1761. This large folio-sized book was produced as a reference book for millwrights and mill owners in the Netherlands. The book’s focus was on the mills that were located in Amsterdam. Johannis van Zyl was a mill maker (the literal translation of the word moolenmaker which features on the first page) from Lexmond, near Utrecht. Jan Schenk was the individual who engraved van Zyl’s drawings onto copper plate so they could be printed in the text. It is thought that Jan was a relative of the publisher of the piece, Petrus Schenk. In the same year, another text similar to van Zyl’s appeared on the market. It was called the Groot Volkomen Moolenboek, which translates to the Big Perfect Mill Book, and was produced by Leendert van Natrus, Jacob Polly and Cornelius van Vuuren. We also hold a copy of this moolenboek at the archive. Both of the texts show how meticulous and detailed the craft of mill making, or millwrighting, was in the early 18th century. Prior to this, mill makers would work from experience and all mills were crafted differently and therefore the knowledge they had was unlikely to be put on paper. In addition, the craft of mill-making was very lucrative in the Netherlands in this period, and therefore mill-makers and their bosses had a vested interest in keeping the process of building wind- and watermills from being widely documented. This text sought to put an end to that, and portray the process of building a mill accurately and clearly. |

The copy of the book we have in our collection is extraordinarily large, measuring nearly two foot high. As it is very large in size, the book features highly detailed drawings of a variety of mills.

Image of the Moolenboek to show its size

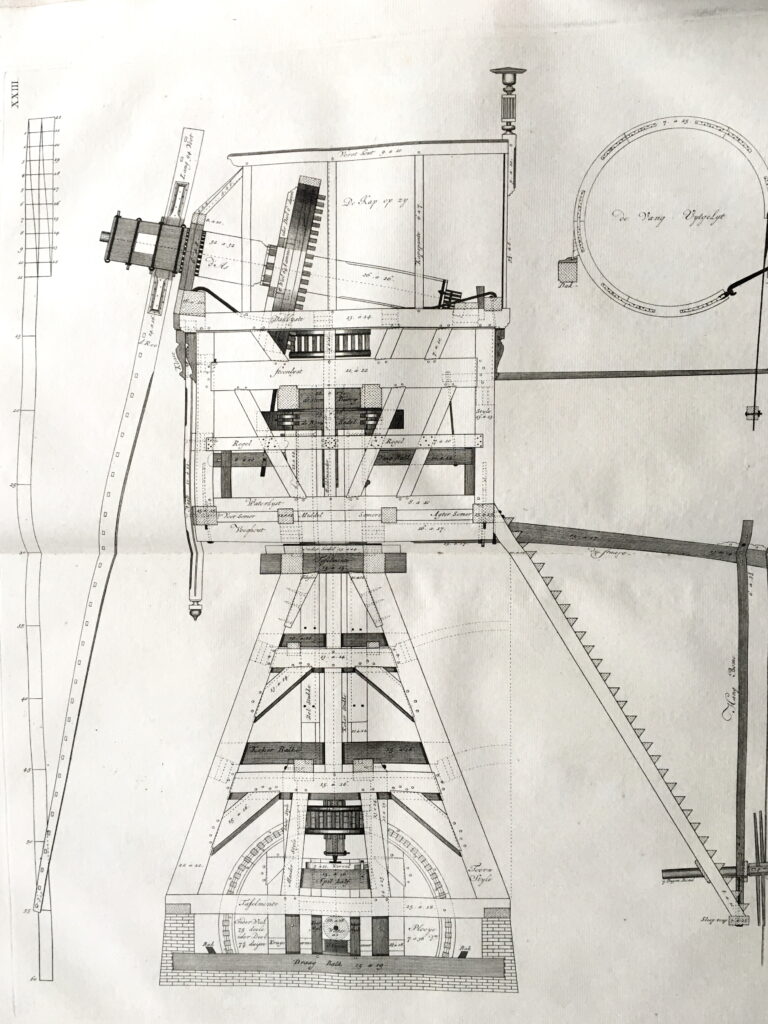

| The windmills that feature as diagrams are oil, tobacco, fulling mills. There are also diagrams of water, saw and lastly modder, or mud, mills, which were used to de-sludge ditches and ponds, in van Zyl’s work. The exquisite drawings are numbered with a reference guide that describes, in what could be labelled as old-fashioned Dutch, the purpose of the drawings and what they are displaying. Almost all of the drawings depict the inner workings of the wind- and watermills of which they represent. |

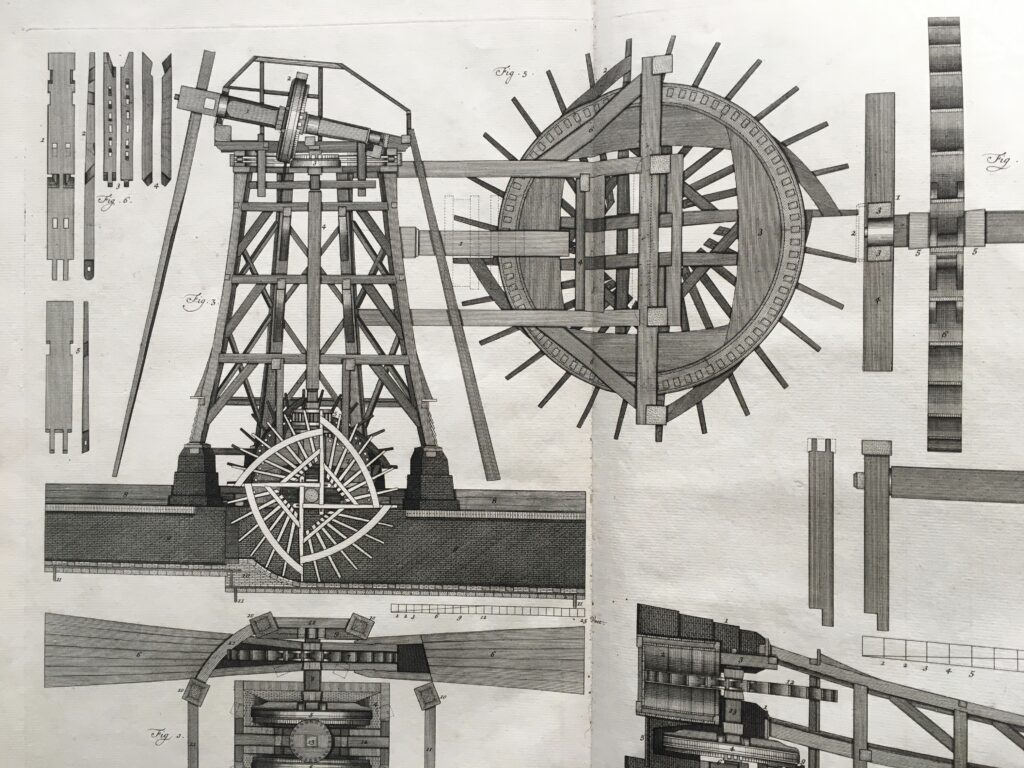

This image here, referenced as XXIII, is a highly detailed diagram of the mechanics of a drainage mill. It offers an insight into the structure, and how the mill is supported from ground level up, as well as showing, in detail, the cogs and the water wheel that features at the bottom of the mill. Van Zyl offers the measurements of all the important components of the mill, which would allow for repairs of the mills in the drawings. It could also have been used as a reference point for building different types of mills, as it spanned a variety of types.

All of van Zyl’s drawings offer measurements, which seem to be in feet and inches. This is assumed as a Dutch carpenter, Paul Aafjes, in 2018 used the Natrus and Polly moolenboek as a guide to help reconstruct gears for a hemp beater in Zaandam.

He is quoted in saying [as translated from Dutch to English] ‘We have calculated everything back to centimeters, because all sizes are still indicated in feet.’ This shows how important these mill books are to the art of mill making today, as they can still be used as reference points for repairing and restoring mills, as well as offering an insight into the history of traditional milling in the Netherlands.

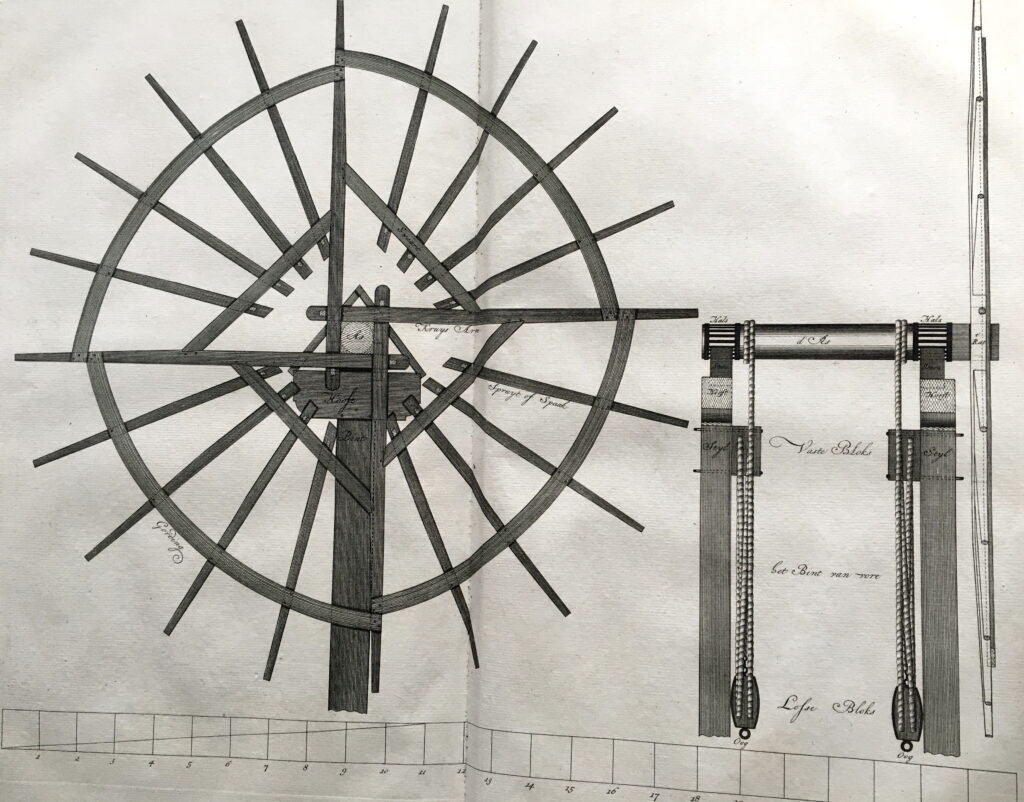

| A feature of van Zyl’s Moolen-boek was the appearance of a paddlewheel, which was designed in a fascinating way. As evident in this image of a watermill, the wheel is shaped in an almost geometric pattern, with the no two parts of the frame overlapping. It is likely that this design of the wheel meant that it had longer paddles at certain key points during the motion of its turning and therefore it could more efficiently process water when the mill was working. Thankfully, the diagram indicates to us that the mill was probably used for drainage. We can identify an elevation in the floor at the bottom of the mill, just under the waterwheel. The water would then flow towards the wheel from left to right, taking the wheel round, by its long paddles, and the wheel would push the water down into the mill race which was deeper than the original millpond. This in turn, would create power and start the mill working. Drainage mills were, and still are, extremely important in the Netherlands as a third of the country sits below sea level. This type of waterwheel is no longer constructed in the Netherlands, though its influence is still apparent. In the township of Leeuwarden, at the De Himriksmole mill, you can find a similar waterwheel. Though it is built slightly differently, the influence of the 18th century and earlier paddlewheel is evident. You can find this picture of the paddlewheel at the bottom of the page here. |

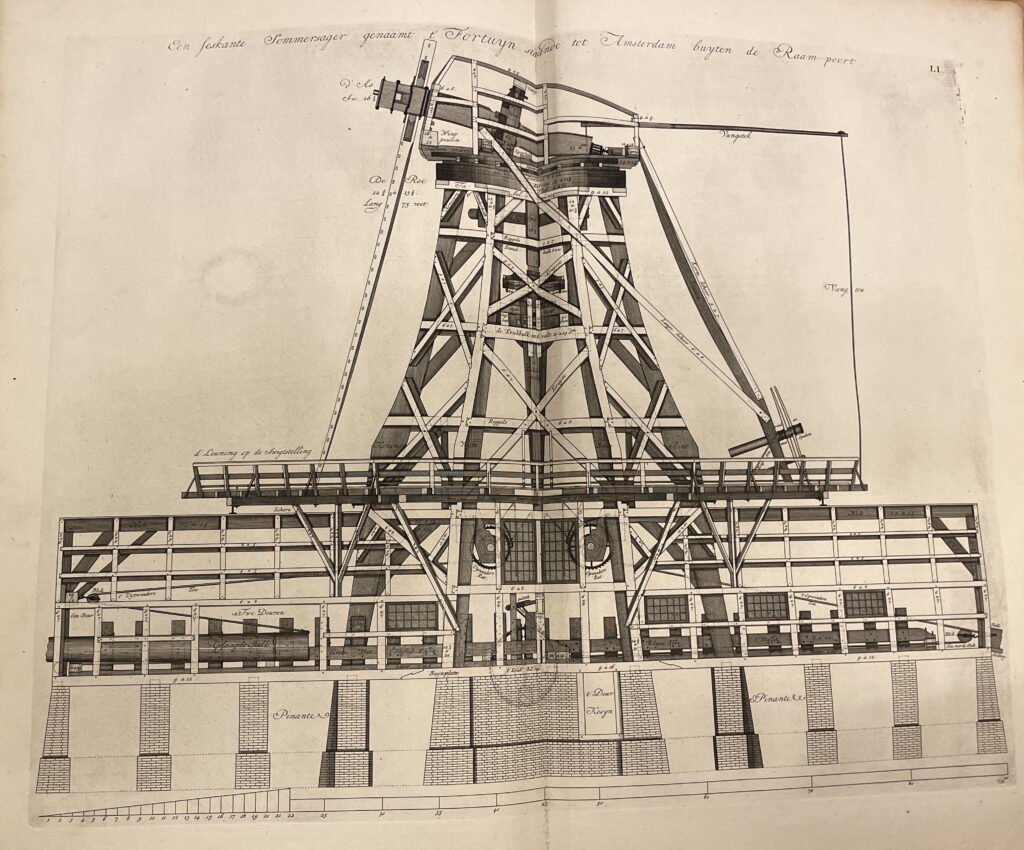

| One of van Zyl’s drawings depicted a sawmill that he helped to rebuild himself, rather than one he measured and drew. The sawmill, named t’ Fortuyn, stood on the Kostverlorenvaart in Amsterdam outside the Raampoort. In 1733, van Zyl rebuilt t’ Fortuyn as a smock mill for Dirk van de Plaat. |

| Though it is difficult to figure out the scale of the drawing – the whole book is in Dutch and my Dutch skills are sub-par – it is clear to see that the saw mill was an extraordinary feat of craftsmanship. The sails extended to 75 feet, and the mill contained multiple floors to hold the machinery necessary for it to be a working saw mill. The saws of the mill are shown quite clearly, and though van Zyl does not offer the measurements for their size, all of the relevant structural features of the mill, such as the upright shaft and the tailpole, have measurements. The drawing depicts the mill in working order with a log on the pulley about to be sawn into whatever sized planks were needed. The fact that this diagram was made in such detail, and from a mill that van Zyl actually rebuilt a year prior to the publication of this text shows the importance of such mill books in the history of millwrighting and mill making. |

| Mill books of the early 18th century provide a fascinating insight into the craft of Dutch millwrighting, or mill making as it is translated. As the first of their kind, they provided a collection of diagrams and drawings which showed the different types of mill and explained how they were built and the measurements needed to construct them. Not only can this assist millwrights today, it provides an important education about the traditional craft. A portrait of Rex Wailes we have here at the archive shows him consulting what is possibly the same book over a cup of tea. This shows how important and interesting the Moolenboeks were to an engineer or mill maker. Though they are focused on wind- and watermills in the Netherlands, and written entirely in Dutch, they still offer anyone interested in the history of the craft an insight into how an earlier version of the mill was created. |