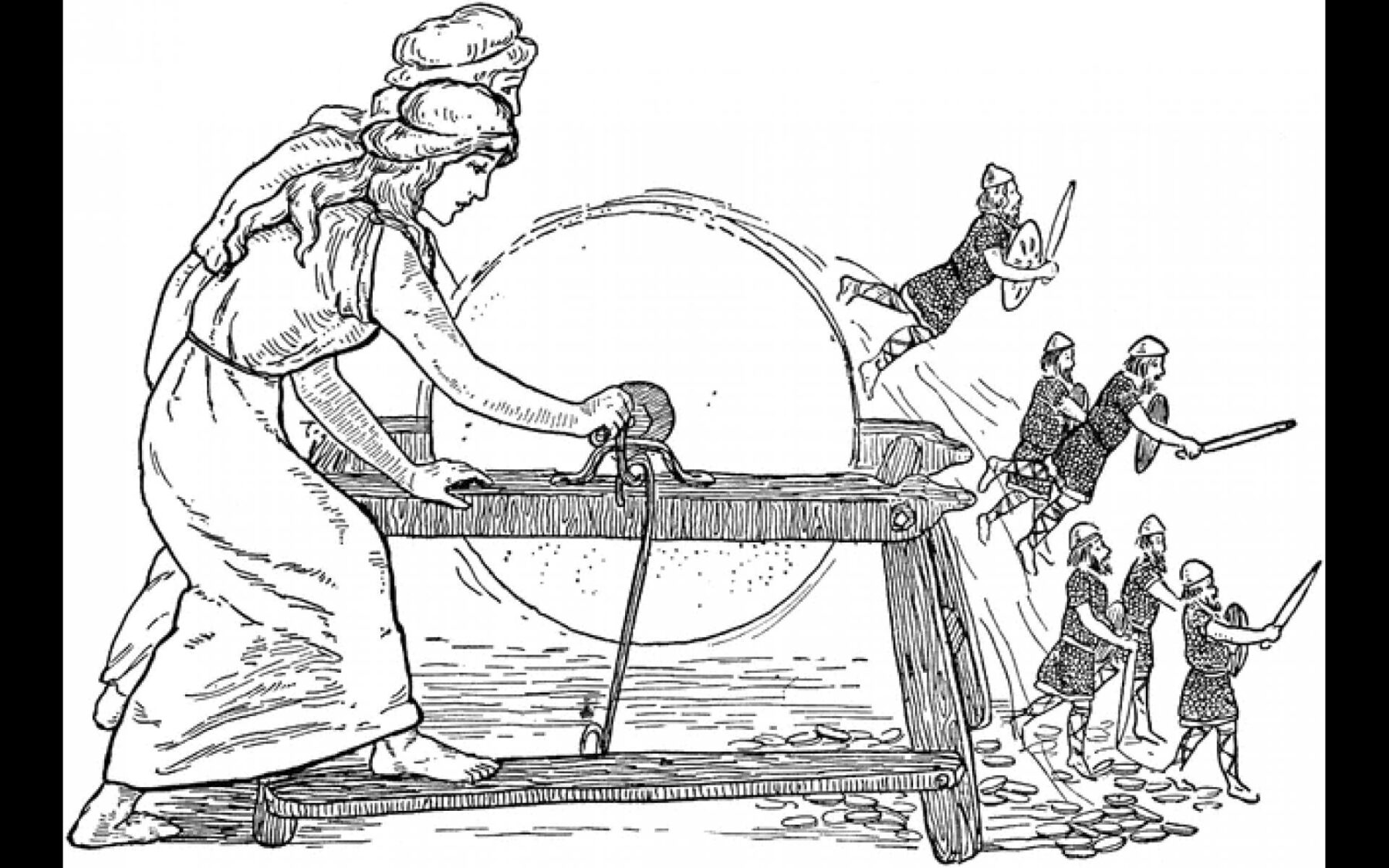

| Mills have often featured in myth and legend. One ancient Norse poem, the Grottasongr or Lay of Grotti tells of a magical handmill, Grotti (literally ‘grinder’). So large that only the giants could turn it, the mill when ground could produce anything you wanted – wealth, peace, happiness. The mill belonged to a king of Denmark named Frothi (‘the wise’), a ruler renowned for the peace of his reign: …and because Frothi was the most powerful king in all the Northern lands, peace was named after him wherever the Danish tongue is spoken, and all people in the North call it “The Peace of Frothi.” As long as it lasted, no man harmed the other, even though he met the slayer of his father or of his brother, free or bound. At that time there was no thief or robber, so that a gold ring lay untouched for three years by the high road over the Jalangr-Heath. But peace never lasts, especially in the world of Norse mythology, where the king of gods, Odin, is always looking to stir up war, so as to increase the number of slain warriors in Valhalla in preparation for the final battle, Ragnarok. It is Odin in disguise who gives Frothi the magical mill, and who also sells him two slave girls strong enough to turn it, Fenia and Menia. The Lay of Grotti consists mainly of the song that they sing while turning the mill – |

To moil at the mill, the maids were bid

To turn the grey stone, as their task was set

Lag in their toil, he would let them never

The slaves’ song he unceasing would hear

Painting of Grotti by Carl Christian Peters (1822–1899)

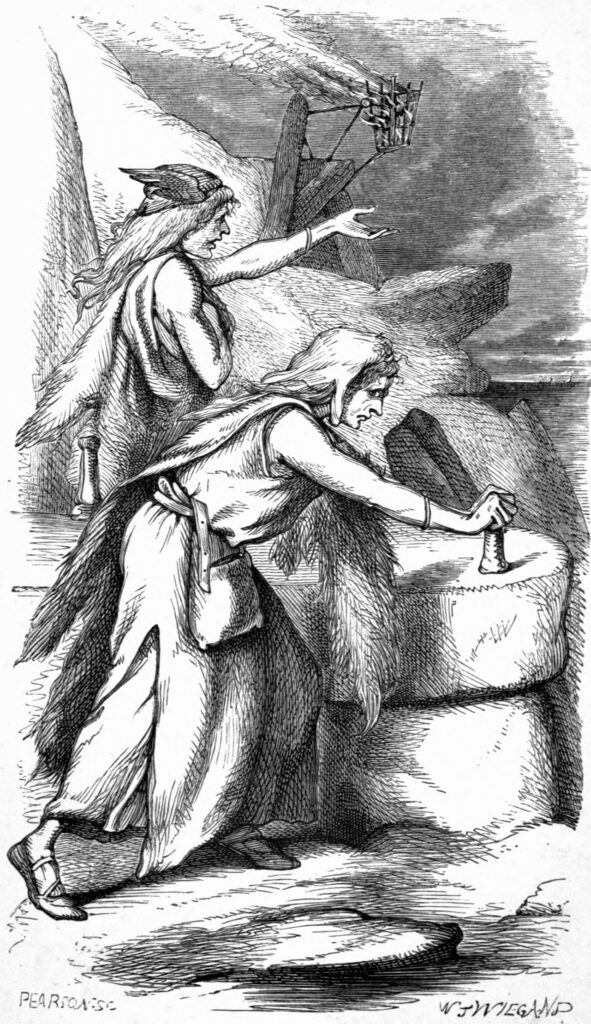

| At first they sing about the wealth and prosperity that they are bringing to Frothi, but then their song becomes more ominous. The slave girls reveal that they are daughters of the giants – in fact, as children they created the quernstone: Winters nine we grew beneath the ground; Under the mountains, we mighty playmates Did strive to do great deeds of strength; Boulders we budged from their bases, Rocks we rolled out of etin’s realm, The fields below with their fall did shake; We hurled from the heights the heavy quernstone, The swift-rolling slab, so that men might seize it. |

| The slave girls then recount how they became Valkyries, and recite their deeds on the battleground, before lamenting their enslavement: Now we are come to the king’s high hall, Without mercy made to turn the mill; Mud soils our feet, frost cuts our bones; At the peace-quern we drudge; dreary it is here. By this point it seems the king has fallen asleep. The slave girls now determine to get their vengeance – instead of peace and wealth, they grind out war and destruction: |

My eye sees fire east of the castle;

Battle cries ring out, beacons are kindled!

Hosts of foemen hither will wend

To burn down the hall over thy head.

It seems that Frothi gained the throne by killing his brother, Halfdan, and his relatives are coming to seek vengeance. The events are referred to in more detail in other, sometimes contradictory, Scandinavian sources, as well as the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf. Interestingly, in Latin versions, the name Frothi is rendered as Frodo, which was J R R Tolkien’s source for the name of the character in The Lord of the Rings.

But the story of the mill wasn’t over. Although in the poem, it seems the efforts of the slave girls have broken the mill apart, a later version gives a different account. Here it was Mysing, a sea king (ruler over a fleet of ships) who defeated Frothi, and took the mill and the slave girls with him. As they sailed away, he asked them to grind salt. They ground until the ship sank beneath the weight of the salt. The mill sank to the bottom of the sea, still grinding salt – and that’s why the sea is salty.

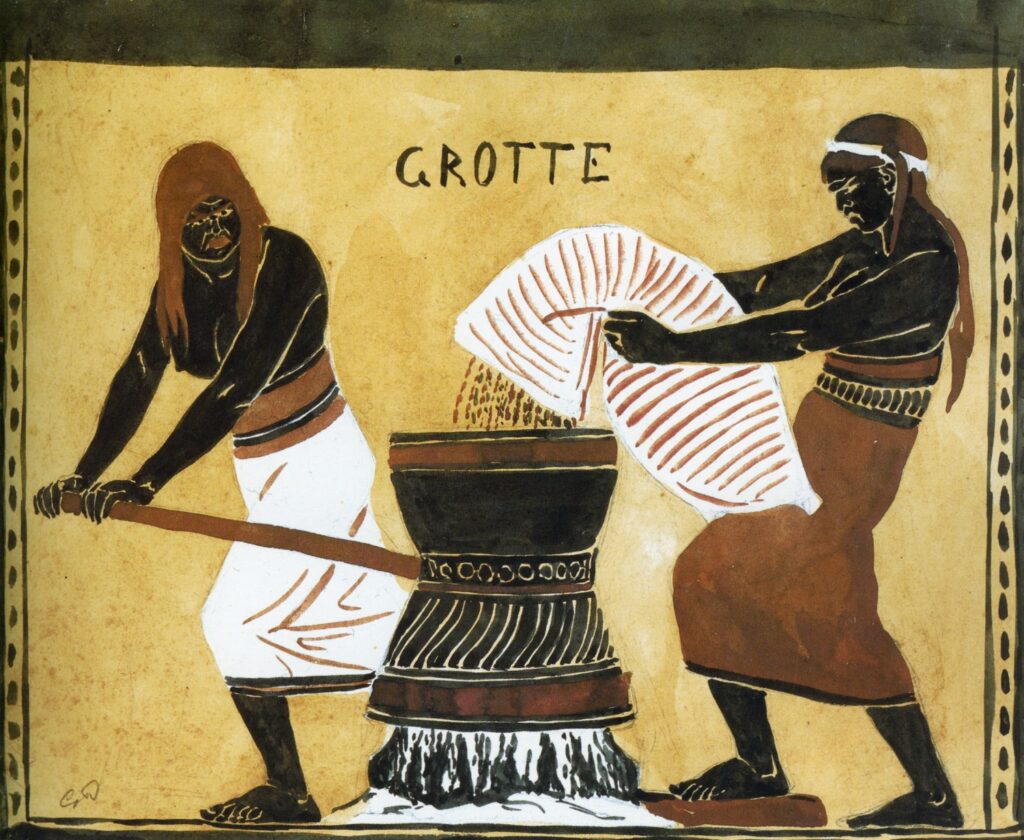

Illustration from an 1871 book

| The motif of a mill that grinds salt on the seabed is found in numerous fairy tales. A whirlpool in Pentland Firth in the Orkneys known as the ‘Swelkie’ (from the Old Norse Svalga, ‘swallower’), is sometimes said to be the spot where the mill still grinds on. |

| Quotations from The Poetic Edda, trans. L Hollander (1962, University of Texas Press), p 153. |